In 2018, the WA Government sought community views about the proposal. Feedback was provided by a range of individuals, groups and government agencies, just under half of whom were Aboriginal people or organisations.

In total, it received 77 written submissions and held 43 verbal discussions about the proposal. In July 2019, it released a Community Feedback Report, which outlined the main ideas and concerns raised through the feedback process.

Feedback received in response to the discussion paper will now inform a model for the new office that will be considered by the Government. It is anticipated that new funding and supporting legislation will be required, therefore the proposal will be contingent on budgetary and Parliamentary processes.

Executive Summary

Show moreIn 2018, the State Government sought community views about a proposal to establish an independent statutory office for advocacy and accountability in Aboriginal affairs. Feedback was provided by a range of individuals, groups and government agencies, just under half of whom were Aboriginal people or organisations.

Views on the proposal in general

- The vast majority of responses favoured the proposal, although many emphasised that it should be “done properly”, be well resourced, and that Aboriginal people should be heavily involved.

- Some respondents were concerned that the proposal might not deliver its aims, and a small number stated they would rather see the Government prioritise other ways of improving outcomes for Aboriginal people.

What should be the role of the new office and how should it be set up?

- Most responses agreed that the office should be free to determine the scope and extent of its business in conjunction with Aboriginal people, and that its key functions should be advocacy and accountability.

- Some submissions stressed the importance of Aboriginal people having an easily recognisable, approachable and culturally safe agency they can contact with their concerns.

- Many stated that the office’s main business should include:

- engaging with Aboriginal people and helping to build community capacity

- making recommendations on government policies and programs

- promoting Aboriginal culture and achievements, and meaningful engagement by government agencies.

- Respondents agreed that the new office should be independent and established under legislation. Some thought that all or most of the staff in the office should be Aboriginal.

- Having a regional presence or network was stressed as important, to account for the diversity of Aboriginal people across Western Australia.

- Most agreed that the office should be accountable to Parliament and Aboriginal people.

- Some submissions recommended having two key office holders - a man and a woman for reasons of inclusiveness and cultural protocol.

What should this new office be called?

- A number of names were proposed. The term 'Commissioner' was widely endorsed.

- There were diverging views about 'First Nations' and 'Aboriginal'.

- Using words or phrases from a specific Western Australian Aboriginal language was not recommended, as it would not be inclusive of the diversity of languages across the State.

- Feedback largely supported Aboriginal people being involved in deciding the name.

How should the new office holder be appointed?

- Almost all responses agreed that Aboriginal people should be involved in the appointment process. Many thought this should include developing the selection criteria and choosing the successful applicant.

- A selection panel drawn from respected Aboriginal people was a common suggestion.

- It was agreed that the office holder should be an Aboriginal person from Western Australia.

What next?

- The Government is now considering the extensive feedback received as part of the first stage of consultation.

- A report will be released providing details on the preferred model as informed by the feedback received during the first consultation process.

- There will then be a further opportunity for comment and consultation before any draft legislation is introduced into Parliament.

Introduction

Show moreIn June 2018 the State Government released a discussion paper proposing an independent statutory office for advocacy and accountability in Aboriginal affairs in Western Australia.

The paper discussed the idea of an office to make sure governments are held accountable for how they work with Aboriginal people in Western Australia, and to speak up about things that matter to Aboriginal people. It outlined how this new office might operate and invited people especially Aboriginal Western Australians to tell us what they think.

This Community Feedback Report outlines the main ideas and concerns raised through the feedback process. Every response was read or listened to thoroughly and this report provides a broad summary of those views. Direct quotes from submissions or consultations have been included where they represent widespread or otherwise significant viewpoint.

About the consultation process

The Government recognises it does not have all the answers on any particular issue, especially in Aboriginal affairs. Consultation is not just about gauging the popularity of a proposal it builds a detailed picture of its possible impacts, helps to refine it and ensures it offers the best possible solutions.

The feedback process commenced on 7 June 2018 with the release of the discussion paper. Copies were sent out, with invitations to provide comment, to a wide range of Aboriginal organisations, including:

- Key Aboriginal peak bodies, advocacy organisations and service providers in each region across the State

- All land councils, native title prescribed bodies corporate (PBCs), and native title claim groups

- All permanently occupied remote Aboriginal communities and town-based reserves

- Statutory Aboriginal boards such as the Aboriginal Lands Trust and Aboriginal Cultural Materials Committee

- National institutions, such as the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies, and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner.

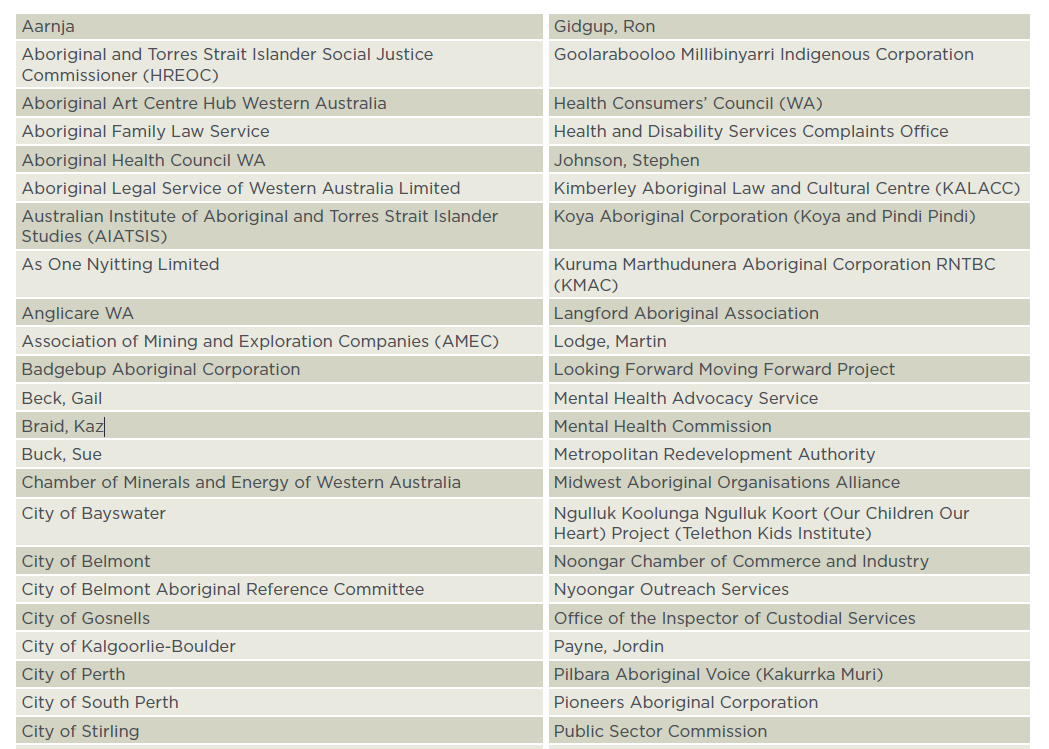

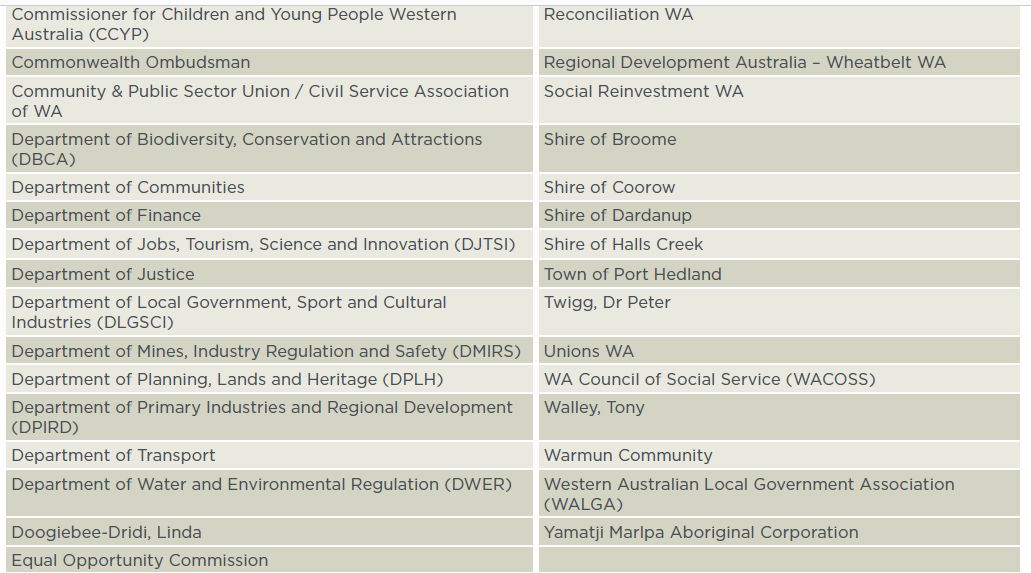

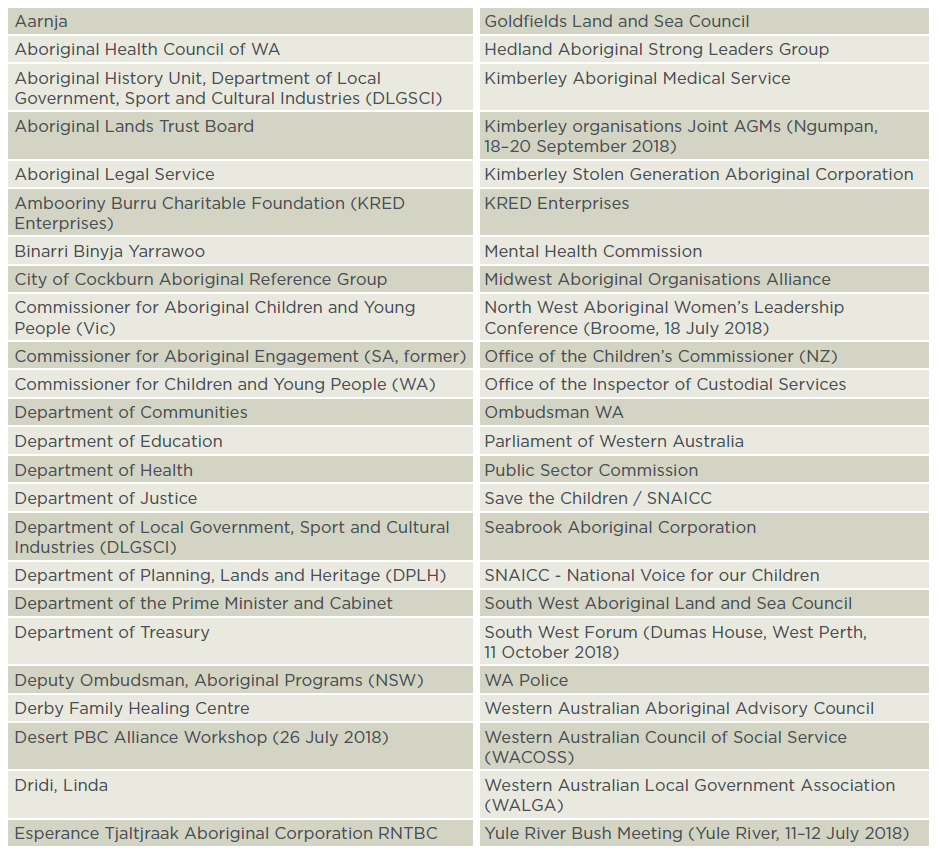

Submissions were also welcomed from members of the public, non-government organisations, businesses, and state, local and Commonwealth governments or agencies. A range of in-person or telephone consultations also took place at conferences, workshops, forums or specially arranged meetings across Western Australia. A complete list of written submissions and consultation meetings is provided at the end of this document as Appendix 1. Written submissions for which we received permission to publish can also be viewed. In total, the Department received 77 written submissions and held 43 verbal discussions about the proposal.

About the feedback

This report is based on all feedback received—written and verbal. Overall, responses varied greatly. Not all submissions addressed the same issues. Some followed the structure of the discussion paper in full, while others only discussed certain components of the proposal.

Just under forty-five percent of those we heard from (53/120) were Aboriginal people or organisations. Some non-Aboriginal organisations also included comments and advice from Aboriginal staff, members and/or reference groups in their feedback. Overall, there was no single, distinct stance or viewpoint evident in these responses. Amongst the feedback received from Aboriginal sources, there were areas of broad agreement and also of clear disagreement; these patterns did not differ greatly from the range of opinions provided by non-Aboriginal contributors.

Views on the proposal in general

Show more

The overwhelming majority of those we heard from agreed that the proposal outlined in the discussion paper is a good idea worth pursuing. Many expressed this support without any qualifications or reservations. Others qualified their support by saying it would depend on things being done the right way, being well resourced, and Aboriginal people being heavily involved. A small proportion were concerned about the particular structure proposed, or suggested that the Government should prioritise other ways of improving outcomes for Aboriginal people.

Numerous responses agreed that the timing is right (or well overdue) for such an office, especially if it ensures that governments respond better to the needs of Aboriginal Western Australians.

We strongly support the proposed office as a means to provide oversight regarding Aboriginal affairs in our State – particularly if the role can deliver long-term and sustained impacts, without being subject to the political cycle. (Noongar Chamber of Commerce and Industry)

[We] support the concept of establishing a permanent entity with statutory powers to lobby for, and advocate on behalf of, Aboriginal people. We believe that if this position is genuinely resourced and supported, and therefore able to move Government towards a position that is more responsive to the needs and priorities of Aboriginal people, it could, as the Government's discussion paper puts it, deliver 'real change in the lives of Aboriginal people'. (Ngulluk Koolonga Ngulluk Koort)

Quite simply, the Aboriginal Affairs system is ineffective and requires significant reform … the Office for Advocacy and Accountability is an essential part of this reform. (Pioneers Aboriginal Corporation)

[The proposed office would] … act as a circuit breaker to implement a new approach to the historical practices regarding Aboriginal Affairs where public sector systems have continued a business as usual approach despite evidence … that what was being provided did not work. ( Midwest Aboriginal Organisations Alliance)

We need to have something in place that can move things a little quicker than what they have currently and in the past. (Ron Gidgup)

We believe an office with the statutory power to investigate and report on systemic issues Aboriginal people can face … would be beneficial in helping to reduce inequity and shining a light on the shortcomings with in our system. (Health Consumers Council WA)

Many viewed the proposal as an important step towards addressing the things that are not currently working. There was hope that changing the way that government engages with Aboriginal people might help Aboriginal people engage better with government.

I think this is a step in the right direction, the treaty direction. We have been in such need of an organisation that [would] make sure the government is listening properly and is accountable to all Aboriginal people across WA. (Jordin Payne)

In the current morass around Aboriginal affairs the theme of 'things are not working' is tremendously common and generates enormous resentment and disengagement. A courageous and sustained effort to confront this reality will be required. Establishment of an Aboriginal Advocacy Office could help lead efforts to confront this reality by opening up space to ask 'why is this not working'. (Dr Peter Twigg)

Some respondents stressed that for it to be successful, the Government must provide the necessary resources and support, engage with and gain the trust of Aboriginal people, and take care to get the processes and structure right.

KMAC is supportive of the establishment of a new office for accountability and advocacy, but reiterates that the success of this office will only come from systematic engagement with Aboriginal people, and with clear channels of communication between the office and Aboriginal people to ensure that Aboriginal people’s interests, issues and concerns are heard, and reflected in policy implementation and service delivery. (Kuruma Marthudunera Aboriginal Corporation)

Rather than ending up as an avenue for Government outsourcing of risk, accountability and responsibility in Aboriginal matters, the new office can potentially revolutionise engagement and relationships between Aboriginal people and the WA Government. However, for this to happen the new office must be independent, highly aware and appropriately informed. (Goolarabooloo Millibinyarri)

A few respondents supported the initiative but contended that the proposed office was only one part of what is needed, the other being the establishment or recognition of representative Aboriginal bodies to take on a stronger role in policy development and implementation, or to advance a treaty process.

Some of those who were supportive of the concept were at the same time wary, concerned that this would end up being yet another “token” initiative that promises to be different but delivers disappointing results.

Don’t set it up as tokenism. We’ve been told too many times that things are going to change. (Jeanice Krakouer, South West Aboriginal Land and Sea Council)

I genuinely hope this consult is not just another bundle of words and a manufactured process – but something that is meaningful, accountable, robust, and truly represents the voice of all Aboriginal Western Australians. (Tony Walley)

I hope it all pans out nicely – it sounds a bit too good to be true. (Participant, City of Cockburn community forum)

Others also questioned whether the office would be focused on Aboriginal people, rather than just on making things easier for government.

A government approach will not work and the new organisation must not be seen as a revamping of government bureaucratic purpose. (Lan gford Aboriginal Association)

There is a real risk that the establishment of such an office will serve to reduce the dialogue to one based solely around the better delivery of services by Government agencies. (KALACC)

A small number of respondents indicated that they were not in favour of the idea overall, preferring to see the Government focus on what they regard as more pressing issues: facilitating and resourcing Aboriginal people to identify and implement their own reforms, strategies and outcomes.

… the establishment of this accountability office may be one small step in that right direction. However, the fear and the concern is that in embarking on this course of action the Government is prioritising an issue of secondary importance – at the same time as we are yet to see progress on critical issues of primary importance and concern. (KALACC)

The new office proposed by the State Government seems to be a dilution of the voices of Aboriginal people in the State. Establishing a single point contact based over 2,000kms from the Kimberley is prohibitive to securing regional partnerships and decision making which is being offered through Aboriginal led processes and Kimberley Futures. (Aarnja)

We also have strong cultural governance in the Kimberley and peak organisations here to represent us. They should not be ignored. They must be respected and included. We question the need for a state advocacy role when we already have these organisations in place. (Ngumpan Statement,20 September 2018 – KLC, KALACC, KLRC, Aarnja)

One respondent queried whether there was any evidence that such an office would have a positive impact on outcomes for Aboriginal people.

The main concern is that the establishment of this office could add another layer of bureaucracy without there being any direct increase on life expectancy, improved health outcomes, reduced imprisonment rates, reduced unemployment, better educational outcomes, etc of aboriginal [sic] people. (Shire of Cooorow)

What should the role of the new office be and how should it be set up?

Show moreFunctions and powers

The discussion paper proposed that the new office would have two main functions; holding government accountable for the way it works with Aboriginal people, and advocating for Aboriginal people and the things that matter to them. Respondents generally supported both of these functions, while some offered refinements, variations or alternatives.

Many respondents expressly supported, and none expressly disagreed with, the proposal for the functions of the office to extend beyond State government to include local and Commonwealth governments as well. (There was broad recognition that some aspects of the proposal, such as the power to compel the provision of documents and information, could not extend to the Commonwealth).

There was a range of opinion on whether the office’s functions should extend to non-government organisations, given the considerable proportion of service delivery to Aboriginal people that is outsourced by government. A number of respondents suggested that the office should have so-called “follow the dollar” powers—such as those of the Office of the Auditor General—to look into the operations of non government organisations contracted by government to provide services. Others considered that there would already be more than enough for the office to do without opening up this additional area of responsibility, and that it would be more effective for the office to focus on the government’s role in the commissioning, procurement, contract management, and evaluation of services.

Accountability

In general, respondents spoke about an accountability function involving monitoring various aspects of government activity and outcomes for Aboriginal people, and publicly drawing attention to instances where improvements were needed - as well as areas of success.

There were different ideas about how this function might work. Some emphasised statistical data, accountability frameworks, and key performance indicators, while others focused on systemic inquiries into particular issues, and receiving feedback from Aboriginal people and organisations about which parts of the system need improvement.

The role of the office must be focused on specific outcomes, with transparent performance indicators established, a clear and meaningful reporting mechanism mandated, and clear timelines, in order to measure effectiveness. (Kuruma Marthudunera Aboriginal Corporation)

We believe an office with the statutory power to investigate and report on systemic issues Aboriginal people can face in our health system would be beneficial in helping to reduce inequity and shining a light on the shortcomings within our system with the aim of quality improvement for consumers. (Health Consumers Council WA)

The office has to be more than merely the advocate and “stone thrower”, but be part of the “solution” or broker of progress otherwise its progress may be compromised. (Anglicare WA)

Some respondents outlined specific aspects of the accountability function they would like to see in place, including:

- Reviewing the effectiveness, efficiency and accountability of services, including a strong emphasis on procurement, service commissioning and contract management

- Monitoring and reporting on the government’s implementation of recommendations from previous reviews, reports and Royal Commissions

- Reviewing Aboriginal employment and business outcomes

- Reporting on the rights of Aboriginal workers in the public and private sectors

- Auditing and improving cultural competency in government agencies

- Assessing government policy’s consistency with human rights, legislative requirements and previous commitments

- Monitoring and supporting investigations of deaths or serious injuries of Aboriginal people in connection with the provision of public services

- Focusing on the use of data and evidence, including monitoring the quality of government data-collection and evaluation practices, and whether decisions are informed by evidence

- Monitoring and reporting on progress in the negotiation and implementation of regional decision-making frameworks such as Empowered Communities

- A role in the Closing the Gap process, involving monitoring progress towards targets.

A report-card model was one method suggested for focusing accountability on outcomes and government performance. However, some thought this may not be effective unless agencies were required to respond to such reports within a reasonable time frame. Others were concerned about the additional reporting burden on agencies.

Many responses stressed that the new office should be able to conduct inquiries and that government agencies should be obliged to provide relevant information. Some were keen to ensure this obligation is backed by enforceable penalties.

Advocacy

Many respondents supported the office using a range of advocacy strategies to drive systemic improvements. Some framed this as an expert “problem-solving” role, engaging with key government decision-makers and helping them identify “what works”. Others emphasised the centrality of working with local and regional Aboriginal organisations, and building community capacity and empowerment towards self-determination.

… it is about fostering communities to thrive and be strong and resilient with the driver being local vision and priorities, and utilising local community assets wherever possible. (Midwest Aboriginal Organisations Alliance)

A significant focus needs to be, therefore, on building effective engagement mechanisms that are based on principles of self determination, are trusted by community and develop local capacity. (WA Council of Social Services)

Some respondents stressed that the advocacy function involves amplifying the voices of Aboriginal people and organisations, supporting Aboriginal people in speaking for themselves, and ensuring that government agencies listen and work closely with Aboriginal people and organisations. Some saw this function as also involving the provision of guidance, advice, capacity-building, networking, and other assistance to Aboriginal organisations in negotiating and implementing self-determination.

A number of respondents considered whether the proposed office might serve as an interface between Aboriginal organisations/communities and government agencies, but it was also stressed that the office should not be used by government agencies as an excuse not to undertake their own engagement processes.

More recently, the Government has disbanded the Department of Aboriginal Affairs, which some have interpreted as reflecting a further downgrading in the level of concern shown for Aboriginal people . The Government should not expect to replace the machinery of a whole department with a single individual or office. Establishing an office for advocacy and accountability in Aboriginal affairs in Western Australia shouldn’t let the government off the hook for not consulting with Aboriginal people about programs and services. (Ngulluk Koolunga Ngulluk Koort)

We suggest that the need for greater accountability and responsiveness to advocacy for outcomes to Aboriginal people needs to be embedded across government, not simply to be allocated as the responsibility of an independent office. (Reconciliation WA)

A significant area of debate was whether the office should have the function of advocating for individual cases. The discussion paper said:

In order to avoid duplicating the work of other agencies, and focus on the activities where it can be most effective, we do not envisage the proposed office would have a role in investigating complaints (like the Ombudsman) or advocating for individual cases (like the Chief Mental Health Advocate). We consider that these functions are best handled by existing agencies who have expertise and resources to focus on their respective areas of specialty. Instead we see the accountability and advocacy office’s function operating at a system-wide level.

While many respondents acknowledged that advocating for individual cases would be very resource intensive and duplicate the functions of other bodies, a considerable number also considered it important for Aboriginal people to have somewhere culturally safe and approachable to take individual issues and complaints an agency that is about them and for them. As it is often difficult for Aboriginal people to know where to turn and who to talk to when they have an issue, some respondents thought having an individual advocacy function, or at least the option to take up such cases, should be considered. This could include following up issues on the person’s behalf, or safely referring them to the appropriate agency.

Systemic advocacy is vital in long term improvement; however, it needs to be acknowledged that our systems are so fractured that people often cannot wait for systemic change, they need and deserve individual help now. We acknowledge the position of the discussion paper in stating that individual advocacy lies with the specialist organisation, however due to funding/role constraints and the complex entanglement of systems who service consumers this is sometimes messy and ineffective f or the consumer. (Health Consumers Council WA)

Aboriginal people and Aboriginal organisations are much more likely to report matters to an office held by an Aboriginal person … and may not be aware of their options to lodge a complaint with a mainstream statutory authority. (Yamatji Marlpa Aboriginal Corporation)

Page 11 of the of the discussion paper refers to an absence of an individual case related advocacy role for the new office and cites existing organisations such as the Ombudsman and the Mental Health Commission that have this function, however how often/extensively do Aboriginal people access these existing systems? I would suggest that access to these existing structures needs to be actively facilitated by an advocacy team with individual cases as part of the role of the office of advocacy and accountability in Aboriginal affairs. (Commissioner for Children and Young People WA)

In order to ensure Aboriginal community support for the office, it is imperative that the office is resourced sufficiently to also perform an effective triage-type referral process. … This process should be undertaken in a culturally competent manner that provides ‘warm referrals’ to other relevant bodies. Including a referral function will enhance accountability because it will provide evidence of systemic issues facing Aboriginal people in Western Australia. (Aboriginal Legal Service WA)

It was also noted that small, local-level issues are often indicators of system-wide issues, and having a central, Aboriginal-focused office keeping data on such cases would make it easier to identify trends and patterns in the system.

I suggest that the office should not be required to advocate in individual cases, [but] should be free to do so. Progress in human rights has often occurred and been dependent on publicising and advocating for an individual case. (Equal Opportunity Commission)

In practice, it is often the individual cases that point to sys temic issues and trigger timely action. Without the 'alerts' provided by individual complaints or cases, a systemic problem may not be noticed for some time or could remain hidden. It is also well recognised that many from the Indigenous community will not approach or complain to mainstream agencies. Facilitating the lodgement of complaints from those communities would be a positive step. (Department of Mines, Industry Regulation and Safety)

Structure

Respondents overwhelmingly agreed that the proposed new office should be an independent statutory authority, protected from the influence and instruction of the government of the day, for reasons of both substance and perception.

Furthermore, if the position and office is viewed by the Aboriginal community to have a degree of separation from Government, this will instil confidence. Conversely, any suggestion that this role is just an agency of Government like any other, then its legitimacy in the eyes of the Aboriginal community will be undermined to the point where they will find it hard to support, let alone own the office. (Ngulluk Koolunga Ngulluk Koort)

Many agreed that the office should be a separate body established by stand-alone legislation, rather than by adapting or expanding an existing entity. However, a small number of respondents thought more discussion was necessary to assess the advantages of this approach compared to, for example, enhancing the capability of existing independent bodies (such as the Ombudsman or Commissioner for Children and Young People) to focus on issues affecting Aboriginal people.

There was general support for a five-year term of office, which would give the office holder longevity beyond the election cycle.

Submissions also emphasised the importance of ensuring the office has an adequate budget and a substantial staff. The Aboriginal Legal Service made special note of the need to have a dedicated fund for conducting inquiries. The Equal Opportunity Commission proposed that there would be some benefit in sharing resources or formal management responsibilities with other similar offices, to reduce the administrative burden on the office holder. Some respondents also recommended that the agency should be staffed extensively, if not entirely, by Aboriginal people.

Collaboration, data sharing and complementary work processes were recommended to help deal with overlaps with the business of other agencies. The Commissioner for Children and Young People proposed an additional new office holder, Deputy Commissioner for Aboriginal Young People, who could work across both offices. The Health and Disability Services Complaints Office anticipated that the proposed office could make people more aware of their own services, and thereby 'minimise service delivery gaps to Aboriginal people'.

Given the importance of engaging and consulting with Aboriginal communities and organisations, a number of submissions stated that it would be important for the office to establish a presence not just in Perth but right across the state, to establish consultative networks, even permanent offices, in regional centres. Several respondents also emphasised that the office’s engagement should not be limited to Aboriginal organisations, but should also include getting to know people at 'grass roots' level and seeing first-hand the effects of government policies and programs. Some respondents were concerned as to how this could be achieved by a relatively small organisation, given the need for “boots on the ground”, especially in remote communities.

The new Office can’t just operate with a few people in a central office, thinking and talking policy without connecting with the people impacted by their work. They need regionally based staff, not just FIFO. They need staff who see the value in building relationships, ‘cup of tea’ time, if they want to really be able to address the policy changes. (Indigenous CPSU member)

There will also need to be a commitment and buy-in from Aboriginal communities and organisations as well. The current situation is not just a one-way street and if the new organisation identifies issues in respect to Aboriginal communities and organisations, then they need to be prepared to respond accordingly. (Shire of Halls Creek)

Respondents also stressed the importance of the office holder having the benefit of advice, guidance, feedback (and, in a few cases, oversight) from a group of respected Aboriginal people from across the State. This concept was variously described as a panel, reference group, or in a few cases a board of management. The common element to all of these recommendations was the establishment of channels of information between the office and communities, and the provision of reliable and culturally informed insights into specific issues or areas.

[A] reference group would guide and advise the office holder so they understand the distinct cultural, social and economic interests of local communities. (Yamatji Marlpa Aboriginal Corporation)

This could be a group of representatives, possibly appointed or elected on the basis of their regional associations or expertise, and could include a mix of community leaders and people with cultural authority. Some respondents proposed that the Western Australian Aboriginal Advisory Council (WAAAC) fulfil this role. Others felt it would be important for the office to have direct access to the voices of grassroots people, so that there would be greater understanding of everyday issues. This might include regularly scheduled community visits or forums.

Mechanisms to ensure the Aboriginal voice is heard, from across all regions, is a key imperative for the new office. (Aboriginal Health Council WA).

The disconnect of government and heavily funded non-Aboriginal agencies;… is a reality unless our people are afforded the time to be truly engaged, listened to and then skilled and empowered to make sustainable changes in their own lives with their family, kin and local communities. These families are often missed by government and non-Aboriginal agencies because it is all too easy to give credit to the elevated voices in our community and they may not necessarily reflect the worlds in which vulnerable and socially isolated individuals and families live. (Koya & Pindi Pindi)

Decisions need to be made in recognition of demographic variation – many different communities with complex and varying needs – need strong advocacy for all communities – not just those located close to economically viable towns. (Shire of Halls Creek)

… 'genuine engagement' should include direct engagement and involvement with people at a grass roots level. (Goolarabooloo)

A number of respondents were concerned that this might be too big a job for just one person, even with a dedicated staff. Given the range of issues, and the strong emphasis placed on direct engagement with Aboriginal people, some thought that a network of assistant commissioners or a panel of regional representatives might be a workable solution.

Having two key office holders, one man and one woman, was also proposed, to ensure that all voices are heard equally and that there are no cultural barriers to certain issues being raised and acted upon.

Whilst the discussion paper suggests a single individual as an office holder, we recommend the appointment of a female and male Commissioner to work together would better support equal representation. Members of the Aboriginal community have voiced concerns that historically women’s and children/young people’s interests have been disregarded, in favour of strong focuses on Native Title, mining and land and men’s issues. (Social Reinvestment WA)

And, while we also strongly agree that appointed persons must be Aboriginal and from Western Australia, we recommend that two office holders – one male and one female, as per cultural protocols – share the responsibility of running the office. These persons must also possess a recognised level of cultural authority apposite to their responsibilities.(Pilbara Aboriginal Voice)

However, others considered the potential complications of having two principal office holders to be too great, noting that there are other ways of addressing such issues.

I can see the need to make sure men’s and women’s issues don’t get overlooked, and also to allow proper culturally appropriate communication with men and women. But ultimately, you need to have the buck stop with just one person, with no ambiguity. You don’t want a divided voice at the top. And in any case the office holder needs to be able to think and act across all groups, not just themselves whether it be their region, their language group, their gender. (Gail Reynolds-Adamson, Esperance Tjaltjraak RNTBC)

Accountability of the office

Feedback supported the proposal that the office and the office holder should report directly to Parliament, or to a dedicated Parliamentary Standing Committee, by tabling its reports and findings.Respondents also thought it was important that the office be accountable to Aboriginal people. As one submission put it:

Nothing about our people without our people. (Aboriginal Family Law Service)

Submissions stated that the office-holder should have the endorsement of Aboriginal community members and should provide information back to Aboriginal people to show where progress is being made and, if not, why. Some suggested that the office should report to a panel or group of Elders or representatives of Aboriginal organisations. A few advised that the WAAAC would be an appropriate body for this purpose.

It was emphasised that the office should be transparent and clear in what it is doing and how it is progressing. Some submissions stressed that the office holder and agency staff would need to be clear about any potential or perceived conflicts of interest. The importance of having clearly defined Key Performance Indicators for the office, designed in collaboration with Aboriginal people, was also identified.

Important things to consider

In addition to the functions, powers, structure and accountability of the proposed office, submissions raised a range of other factors for the Government to consider, including:

- Ensuring Aboriginal culture, including respect for Elders and cultural authority, forms the fundamental framework for how the office operates

- Ensuring women’s and men’s perspectives and issues are given equal emphasis, and giving special attention to the needs of children and young people

- A decentralised structure, which recognises and operates according to the regional, even cultural diversity of Aboriginal people in WA

… facilitating input from Aboriginal people is common, but using the input to shape what actually happens is rare and is what matters. There is no point in engagement unless the system allows the engagement to shape policy and administration to meet local needs. This focus should be emphasised in the functions of the office. (Reconciliation WA)

The Government should work with Aboriginal people to develop and to implement regionally based planning frameworks and governance systems. (KALACC)

Compel government agencies to collect data on the outcomes for Aboriginal people in their system in a way that reflects the needs and organisation of the Aboriginal community rather than the colonialist divisions of the State. That is, according to Aboriginal cultural blocs rather than the current meaningless regional structure. (Pioneers Aboriginal Corporation)

It was heavily emphasised that gaining and maintaining the trust of Aboriginal people, who have been let down and left disappointed by past government policies and actions, would be a considerable challenge.

For the office to have any form of legitimacy with WA’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people it will need to build trust through its own performance and relationships with the people it represents. Simply appointing an Aboriginal person or a council of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people to lead will not be enough. (Regional Development Australia – Wheatbelt WA)

Some submissions stressed the importance of the office not creating an additional layer of bureaucracy, or excessive overlaps with existing agencies and Aboriginal community organisations. It was suggested that protocols could be developed to ensure that issues are dealt with in a streamlined and logical manner.

During the consultation process, a proposal was made to appoint an interim office holder before the legislation is drafted, both to lead the process for the office’s development and to perform some of its substantive functions. The rationale for this proposal was that establishing a new statutory office will take time, requiring the drafting and passage of legislation, the appointment of the office holder and the recruitment of staff. During that time, the gap in the State’s existing accountability framework will remain unfilled. In response to this proposal, some people raised concerns about risks that have to be weighed against the advantages. In particular, the risk of the community’s confidence in, and understanding of, the office being weakened by the interim office holder lacking the legal powers and formal independence that necessarily depend on legislation. No decision about any proposed interim office holder can be made before the Government formally decides whether to proceed with establishing the proposed office.

What should the new office be called?

Show moreThere was a variety of views as to what words should or should not be included in the title of the office, what meanings should be embodied, and whether or not words from a particular Aboriginal language should be used. Respondents also felt that the name should be a concise, clear reflection of the purpose of the office, and that Aboriginal people should be consulted in the naming process.

A number of Aboriginal respondents favoured the phrase 'First Nations' as an inclusive term that recognises Aboriginal people as the first inhabitants of Western Australia and symbolises the commencement of a new relationship.

'First Nation’s Voice'… gives appropriate recognition of Aboriginal people as original inhabitants… (Nyoongar Outreach Services)

… the non-Indigenous power structure in Australia is beginning to acknowledge our First Nations identity. The language is important in recognising, respecting and validating the experience of Aboriginal people… this name may go some way in addressing some of the barriers to Aboriginal people trusting and engaging with such an office, in that it would immediately set out a distinction … (Mental Health Advocacy Service Aboriginal Advocate)

The use of Aboriginal/Indigenous is a colonial term that seeks to homogenise First Nations people (Jordin Payne)

Other Aboriginal respondents felt the term 'First Nations' is associated with Indigenous people in North America, and that the word 'Aboriginal' is more applicable to Western Australia:

Australia has a diverse range of Aboriginal languages and consideration must be given to some groups that don’t speak English as a first language. In our experience all Aboriginal people within WA understand the meaning of “Aboriginal” and whilst they might not know the meaning of “ Advocate” without proper explanation, they will have no trouble identifying that the position is about something to do with them. (Badgebup Aboriginal Corporation)

While some liked the idea of using an Aboriginal word or phrase in the title, many advised against it, concerned about the perception of favouring one particular language group or area. Others stressed the need for the name to be inclusive, welcoming, meaningful and empowering for Aboriginal people. Rather than a specific language, a few suggested using something symbolic that unites and represents all Aboriginal people in Western Australia.

A number of respondents approved of the word 'Commissioner', noting that it represents authority, independence, and carries a great deal of “clout”. Western Australia’s Equal Opportunity Commission also recommended the term, but warned that for some Aboriginal people it may have uncomfortable associations:

The word ‘Commissioner’ appears to have a meaning well understood by the community as an independent person and there are precedents for its use throughout Australia. A possible disadvantage is that i t was used previously in the title of the Commissioner for Native Affairs and may still have negative connotations for Aboriginal people. However, other things being equal, I suggest the title include the word Commissioner. (Equal Opportunity Commission)

The following list shows all the names people have suggested. Some of them were similar enough to be merged into a single name:

- Aboriginal Advocacy Commission/Office, Office of Aboriginal Advocacy

- Aboriginal Human Rights Commission

- Aboriginal Social Justice Commission

- Aboriginal Voices Advocate

- Advocate for Aboriginal Affairs

- Advocate for Aboriginal Concerns

- Advocate for Aboriginal People

- Countrymen of Western Australia

- Commissioner for Aboriginal Affairs / Aboriginal Affairs Commissioner

- Commissioner for Aboriginal Empowerment

- Commissioner for Aboriginal Families

- (Independent) Commissioner for Aboriginal People

- Commissioner for First Nations Advocacy and Action

- Commissioner for First Nations People

- First Nations Advocacy Voice

- First Nations Commissioner

- First Nations Voice

- First Nation Commission of Self-Determination in Western Australia

- Office of First Nations

- The Voice of Aboriginal Western Australia

- Western Australian Aboriginal Accountability Office

- Western Australian Aboriginal Advocacy Commission

How should the new office holder be appointed?

Show moreThe discussion paper proposed that the new office would consist of a single office holder with a supporting staff, and that Aboriginal people and organisations should have a role in appointing the right person for this position. The feedback broadly endorsed this approach (save for the suggestion by some that there should be a male and a female office holder). Respondents also provided advice about who should be involved, what the process should be, and the ideal qualities of the appointed person.

Who should be involved?

Almost all responses agreed that Aboriginal people should be involved in making this decision, although there were varied views as to how this should occur. A few stated that, for the very first office holder, it would be quicker and easier for the Minister for Aboriginal Affairs or Premier to simply decide on the best person, and then build up a stronger process for later appointments. Most, however, felt that giving Aboriginal people a say on who should be appointed – including the initial office holder – would be vital to the legitimacy and sense of Aboriginal ownership of the office.

We believe it is critical that Aboriginal people have a say in who is selected for this important role. Again, this will serve to increase the legitimacy of the office in the eyes of Aboriginal people, and differentiate this proposal from the numerous policies and processes of the not so distant past that have been imposed upon Aboriginal people with little or no consultation. (Ngulluk Koolonga Ngulluk Koort)

[The process should be] devised, led and implemented by Aboriginal people, with and for Aboriginal people. This approach would ensure that the new office is built on principles of self-determination and founded on a strong, engaged, experienced and collective Aboriginal voice. (Australian Health Council WA)

However, there were differing opinions as to how this should happen. Several stated that all Aboriginal people in Western Australia should have a say.

… all Aboriginal people in Western Australia should be provided with an opportunity to vote for the office holder if they so wish. Such a process will ensure that the Aboriginal community has trust in the appointment rather than reaching the view that the office holder has been selected because of his or her alignment with the government of the day. (Aboriginal Legal Service WA)

Others, however, warned that a popular vote may not produce the best candidate, while one response suggested publicising a shortlist of candidates with an invitation for people to submit feedback. Many proposed that a panel of Aboriginal representatives could be appointed to help make the decision, provided it truly reflects the regional, social and cultural diversity of Aboriginal Western Australians. Some suggested that panel members could be chosen from representative groups such as native title PBCs and Aboriginal Community Controlled Organisations, while others stressed the importance of cultural authority, advising that Elders be included in the process.

'Accountability’ in particular should focus on cultural accountability. (Unions WA)

Elders know better than any government what they need for communities and who the best Office Holder should be. (Kaz Braid)

As to how this proposed panel of selectors would be formed, suggestions included people of the respective regions nominating preferred candidates, or the Minister or Premier simply appointing them. A few responses indicated that the WAAAC would be an appropriate body to undertake this task.

What should be the process?

Suggestions as to the best process for selecting the new office holder were quite varied. Many followed on from the idea of having a representative selection panel to develop the selection criteria. Some government agencies recommended that the selection criteria for similar agencies, such as the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner, be used to guide this process.

With the selection criteria settled, the process of identifying the best person could be achieved by an expression of interest, nomination, or application process. Some respondents stated that applicants or nominees should have the endorsement of an Aboriginal organisation or community that can vouch for their integrity and capability.

What should be the qualities of the person appointed?

It was extensively agreed that the office holder should be an Aboriginal person

from Western Australia. Submissions also mentioned the importance of that person

having experience of government processes, as well as the capacity and cultural

authority to represent Aboriginal people from all walks of life.

It is our belief that the success of the Office will hinge in large part,

on the selection of an Aboriginal person that understands not just the

Aboriginal context, but also the workings of Government including a

good understanding of government policies and procedures. (Badgebup

Aboriginal Corporation)

Appendix 1

Show moreFeedback conversations, either face-to-face or by telephone, took place

with representatives or members of Aboriginal organisations, non-government

organisations and government agencies, or at forums and events, as

identified below: