The State Law Publisher is the official publisher of all Western Australian legislation and statutory information. The story of the State Law Publisher began in 1870 when the Colonial Government established the Government Printing Office, which in the latter years would change its name to the State Printing Division and State Print before becoming State Law Publisher in 1995.

Influences and beginnings 1800s-1890

Show moreThe Industrial Revolution of the 19th century resulted in many changes globally to the printing industry and saw radical improvements in presses and paper manufacture, platemaking and typesetting. In Western Australia, the first printing press arrived in 1831 leading to the production of its first printed newspaper, the Fremantle Observer. Before this, newspapers were handwritten. The same press was also used to publish the first book in Western Australia in 1835.

A second press was acquired by Governor Stirling – a Stanhope Hand Press - in 1832, with newspaper proprietor, Charles McFaull, given responsibility to publish Government notices in his newspaper, The Perth Gazette and Western Australian Journal from 1833. In 1836, the Government began printing The Western Australian Government Gazette as a separate issue from the paper with McFaull designated as Government Printer. After McFaull died in 1846, his widow Elisabeth secured the tender for Government printing which she maintained until 1848, then leaving the Colony for good in 1849.

The Survey Department was then given the Stanhope Press and with it the task of printing for the Government departments including maps and postage stamps, but not the Government Gazette which was contracted out privately to Alfred Shenton from 1850 to 1857. With the introduction of convict transportation to Western Australia in 1850, the Colonial Secretary shifted the responsibility of Government printing to the Fremantle Prison which had set up its own print shop to provide work and training for convicts. In 1858, the prison started printing Government Gazette which was a weekly publication with the identification “Printed at Convict Establishment” appearing on official notices from then-on.

Convict transportation ceased in 1868, and although there were still convicts at Fremantle Prison, the Government decided to set up its own Government Printing Office. In June 1870, the Colonial Secretary, Fred Barlee, officially appointed Mr Richard Pether as the first Government Printer. Pether had some experience in printing having undertaken an apprenticeship in his youth at the publishers of the Inquirer Newspaper. Also appointed was compositor William Alfred Watson.

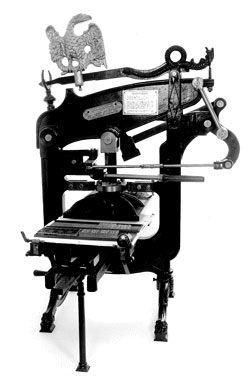

The Government Printing Office had humble beginnings with its first premises, a two-storey building located at the corner of Pier and Murray Streets formerly the Poor House and Women’s Immigration Home. Like the building, plant and equipment was also recycled. Pether and Watson sourced three hand-presses, equipment, type and paper from the Fremantle Prison printing services. On a wet and windy day, 29th July 1870, three small hand presses, including a Columbian Press, were transported by the paddle steamer Puffing Billy up the Swan River from Fremantle to Perth under the supervision of Pether and Watson, the journey taking nearly five hours.

The Government Printing Office was opened for business on Monday, 1 August 1870 and the following day, 2 August, it printed its first issue of the Western Australian Government Gazette No. 31. The appointment of Mr Richard Pether as the Government Printer was also published in this edition of the Gazette. Shortly after another compositor, Johnathon Cousins, started as well as Tom Kerr as pressman/machinist, and apprentices W. McMullen, Charles Bishop and M. Bryan. The original working hours were Monday to Friday 8.00am to 6.00pm and also Saturday 8.00am to 4.00pm, then changing to 1.00pm in 1874.

In 1876, the Legislative Council required the Government Printing Office to print and bind the Parliamentary debates, known as Hansard. This increase in output coincided with the introduction of a printing machine at the Government Printing Office in 1876, the first machine of its kind to be imported into the Colony. Now other jobs were added to the Government Printing Office workload including Parliamentary Bills and Acts, electoral rolls and departmental stationary and even railway tickets with the development of the Fremantle to Guildford Railway from 1881.

By 1881 new presses and a steam engine had been installed and the appointment of its first engine driver, Chas Passmore. The introduction of steam power meant that machines were no longer operated by hand. The increased workload as well as the need to house its new power machine resulted in a need to expand the Government Printing Office premises.

The 1880s also saw the gathering momentum across the board in Western Australia for the establishment of trade unions and for employees to form their own societies, not least of all employees in the printing trade with many having originally come from Great Britain where they were members of Printing Chapels. Chapels, which had a long history dating back to the 14th century, provided a form of self-governance, legislating on both the production and performance of its members and in turn to assist members in times of change, difficulty and industrial unrest. Membership was compulsory for compositors and pressmen permanently employed in the printing trade. In January 1888, the Western Australian Typographical Society was formed to look after workers in the printing industry, being the first recognised union established in Western Australia. Chapels, however, were still regarded as having an important role to play in supporting the work of the union, especially in relation to self-governance and keeping the printing industry a closed shop with union membership being compulsory. The first Perth Chapel was formed at the West Australian Newspapers around 1889. From then on nearly all major printing establishments in the metropolitan and regional areas would go on to have their own individual Chapel, including the Government Printing Office.

A gold and printing boom 1890-1920

Show moreWith the rapid economic and political advances being experienced in Western Australia during the 1890s gold boom as well as with the introduction of Responsible

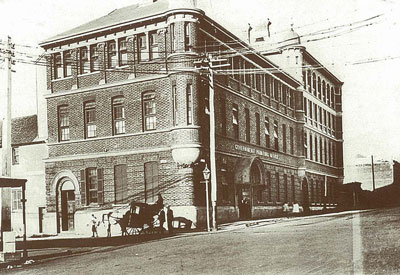

Government in 1890, the volume of work produced in the Government Printing Office and the number of employees increased rapidly. As well as more staff, more up to date machinery, new technologies and production methods were required to be accommodated, such as the replacement of gas with steam to power the new machines. A new building was therefore added to the Murray Street frontage of the original building in 1894; its striking architectural presence dramatically changing the appearance of the Government Printing Office and firming its position as one of the most important public services in the State:

As a result [of the gold boom] Perth gained a new atmosphere of solidity and permanence, a feeling which the State Government wished to portray, and one which was clearly embodied in the style of the new Government Printing Office.1

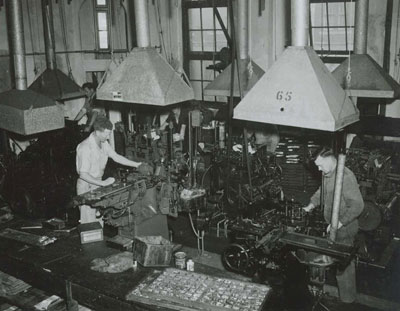

The gold boom had also attracted many compositors into Western Australia to work for the burgeoning newspaper industry, with a multitude of newspapers being established in almost every mining town. The rise of the newspaper sector was aided by the introduction of Linotype machines in the 1890s which were operated by compositors, with Linotype operators quickly becoming one of the highest paid craftsmen and Linotyping regarded as an elite trade. However, many compositors who had been working in the goldfields found themselves out of work, with the newspapers subject to the boom and bust of the mining industry as well as high competition resulting in many having to close down almost overnight. Out-of-work compositors gravitated to Perth with the Government Printing Office an important source of employment, initially as casual staff then gradually taken on full-time. However, the oversupply of compositors soon became a major problem and the amount of employment opportunities became rarer. Compounded with this, all the work required by the Government was now only being given to the Government Printing Office.

Not surprisingly, the appearance of the newly made-over Government Printing Office building in the city along with its exclusivity of work, attracted the ire of the private printing firms and leading stationers of the time who felt that more Government work should be offered by tender to private firms and not be entirely appropriated by the Government Printing Office or, worse, sent outside of the State. This was exacerbated by the fact that staff (mainly compositors) were sometimes laid off by the Government Printer during quiet periods, and were adding to the number of out-of-work printers already walking the streets of Perth looking for work and, not only that, but leaving this “handsome” building idle.These frustrations were vented in Letters to the Editor of the local papers:

Now this to my mind is very inconsistent and unprofitable, and I hope will immediately be remedied by Mr Randell carrying out his original intention and not only that, but give those who are in the colony and contributing to the revenue a chance to remain here by stopping the importation of hundreds of pounds’ worth of work annually from England and the Eastern colonies. It is by many considered a debatable question as to the advisability of the Government entering into competition with private enterprise, but as we have decided that matter by erecting a splendid block of buildings at great expense wherein to do the printing of the colony, then let the Government be logical and make use of it.2

Although the accusations in letters such as this could not always be substantiated and were refuted in replies by the Colonial Secretary, what this example does allude to is the fact that this issue was a point of tension that would remain a thorn in the side of the private sector and continue to dog the Government Printing Office into the next century until it would eventually come to a dramatic conclusion.

In the meantime, the next significant change in the printing industry was emerging. In 1901, the first Monotype typesetting machines were installed in the Government Printing Office. The Monotype machines had been purchased by Pether in 1898 during a visit to England at a cost of £4,000. For the Government Printing Office Monotype was considered more suitable than linotype as it not only produced a better-quality product (such as for textbooks/monographs) but was better for tabular work. However for the newspapers, even though linotype did not produce as higher quality as monotype, the process was quicker and the quality acceptable for the mass production of newspapers. The introduction of Monotype typesetting not only resulted in a radical change in the compositor’s craft but also the amount of work available. Monotype reduced the number of compositors required as they didn’t require manual typesetting which had been the major role of compositors.

When Richard Pether retired in 1901, William Watson was promoted to Government Printer and left in charge of a staff of almost 100 made up of 84 compositors and machinists, and 15 binders working at Murray Street as well as in the separate lithograph department initially established by Pether in a building in Hay Street.

By 1906, Watson had retired and Frederick Simpson was appointed the Government Printer who would have even more new challenges to contend with. Within the first decade of the new century, the technological changes in the printing industry were starting to impact on stable employment opportunities, including at the Government Printing Office. Around the same time unionism was expanding and becoming a stronger force in the industry and for the craft of printing both at the State and national level. In 1910 the Master Printers’ Association was formed which had a main remit of developing a strong sense of craft identity and ensuring the integrity and status of the craft. In 1916, the Western Australian Typographical Society (formed in 1888) became the Printing Industry Employees Union of Australia (PIEUA), Western Australian Branch.

1 Pigeon, John, David Kelsall and Maxine Laurie, ‘Former Government Printing Office, Perth, Western Australia, Conservation Plan’, prepared for Christou Casella & Jee, 2000, p. 7.

2 West Australian, 24 February 1899, p. 2.

A new home and a job for life 1920-1970

Show moreThe Government Printing Office continued to grow during the first decades of the 20th century with more staff employed, new equipment brought in and a third storey

added to the Murray Street building. By now, a great number of staff had notched up long serving employment with the Government Printing Office, some for their entire working life. One of the longest serving staff was Aubrey Curtis who started with Government Printing Office as a probationary clerk in 1878 at aged 18 and retired 47 years later in 1926, which included temporary appointments as Acting Government Printer. When Frederick Simpson retired in 1942, he was at that time the longest serving Government Printer in Western Australia having served 36 years in this role.

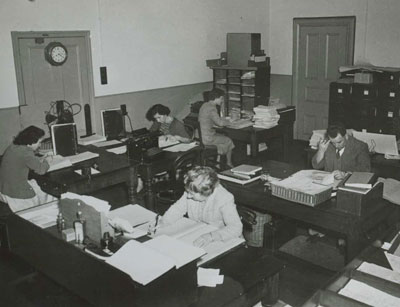

Women were also employed at the Government Printing Office mainly as binding, stapling and folding staff including in the Confidential Department. They also worked in the administration section in secretarial/clerical roles. However, the male and female staff were segregated and had separate works rooms as well as social/recreation spaces, although the women were supervised by male staff. The “Girls Rooms” were located on the third floor and to ensure interaction was kept to a minimum they even had their own private corridor to their latrines. So too, separate dining rooms were provided for male and female staff. However, there were social opportunities for both members of staff to mix with the Ladies’ Dining room, which also had a piano, converted into a hall for social events organised by the House Committee. Other additional services and opportunities provided were a lending library, billiards and smoking rooms.

During World War 2, diminishing supplies of material and equipment on top of reduced workloads and numbers of staff - particularly owing to enlistment in the services - resulted in a hiatus in the development of the Government Printing Office. Those male staff who remained were mainly the highly skilled staff who were required to be manpowered. But with only a skeleton staff, it struggled to keep up with production especially with the allocation of new tasks of producing military maps and plans as well as propaganda material. Security was at a premium because of the sensitive nature of the material.

As the War was coming to an end, there was a lot of catching up to do of Parliamentary papers and annual reports and the need to bring in new equipment to keep up with technology and provide more space for operations and to improve working conditions. Murray Street was becoming too small and production was getting behind and staff struggling with obsolete equipment and facilities. It was decided that it was no longer viable to keep making alterations and additions to the Murray Street buildings, and there were also concerns that the building could not structurally bear the weight of the new machinery which was on order – and not just the machinery but also the weight of the paper.

In 1948, plans were already underway to build new and larger premises for the Government Printing Office, a move that would take it out of the city and into the suburbs.

In June 1949, an area of land totalling 4.5 acres was secured from the WA Government Railways in Wembley on Station Street, conveniently located near to the Subiaco Railway Station and industrial precinct. This was Reserve 22730 which was divided into two allotments; the southern portion Perth Lot 176 originally used as a cattle holding area then later set aside for “Public Buildings” and which was the one earmarked for the site of the new Government Printing Office. The other allotment, Perth Lot 648 on the northern portion, was owned by the Catholic Parish of Subiaco and was where St Josephs’ Church was situated. In 1954, the new St Joseph’s Boys School (later Marist Junior/Preparatory College) and school oval were constructed on the vacant remaining portion of this land.

The acquisition of land and potential to build new and larger offices came just in time as the then Hawke State Labor Government, which came into power in 1953, insisted that all government printing had to be done by the Government Printing Office. However, because of post-war shortages of building material, it would be some years after the end of the War and its aftermath before the move was made.

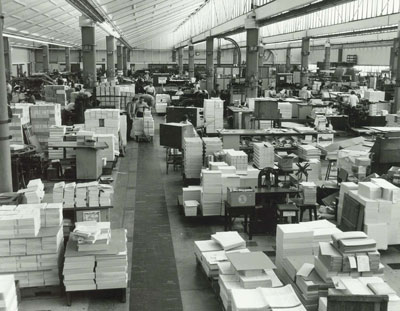

In 1959 the new factory at Wembley was finally ready and after nearly 90 years at Murray Street the Government Printing Office had a brand new home. Unlike its first premises, the new factory had double the floor space and been purpose-built, therefore improving working conditions enormously, and also designed to allow for future expansion. With a capacity now to undertake large print runs, improve efficiency and increase buying power, combined with the robust in-house accounting and costing strategies, print production was not only viable but predicted to increase and be highly competitive.

This new era also saw the appointment of a new Government Printer, Alexander Davies, in 1958 who was in charge of 450 employees. Davies was not only facing new technological changes and the implementation of new processes - such as the replacement of letterpress with offset printing - but also some more social challenges leading to appraisals of staff rules and regulations.

With the rolling in of the 1960s, the social liberations being experimented with and introduced in the broader community were starting to have implications within the walls of the Government Printing Office. With a staff now including approximately 80 women, the rising popularity of the miniskirt was starting to make a noticeable appearance in the workplace. Although there were no rules brought in by Davies to preclude the wearing of miniskirts, once a complaint was received – interestingly not from male staff but the women’s representative of the union - he was obliged to act. The complaint was specifically over a girl occupying a machine whose short attire was distracting men’s attention from their work and potentially putting them in a dangerous position. After going to the department concerned to observe the girl who - fortunately or unfortunately - was at that time standing on a raised platform, Davies in the end agreed that it was dangerous, not just in this situation but could even be a danger in other positions they were hitherto not aware of. As a result, a rule was introduced that female operators had to wear smocks while carrying out positions that may be considered distracting to other employees. Not surprisingly the female operators objected to this ruling, saying that if they had to wear smocks then the female office staff should be made to wear them too. When Davies agreed to this, he temporarily found himself the centre of considerable reactive media attention.

The male staff also had their own fashion issues. Although moustaches had historically been acceptable, the growing popularity of long beards was now finding its way into the Government Printing Office and on the faces of its staff, in particular the young apprentices who usually teamed it with long hair. For reasons of both hygiene and safety, Davies brought in the “no beards” rule under his term, but this would eventually be relaxed under subsequent Government Printers.

However, any minor and short-lived tensions created in the interests of addressing social mores, the Government Printing Office enjoyed continued success at its impressive new facilities and expansion of its services, mainly as a result of its expansion in commercial operations. One of the largest jobs secured was the enormous print runs associated with the publication of the State’s telephone directories which kept the printing operations more than viable. Other work secured included the Streetsmart street directories, school texts, exercise books and annual reports. So too, the amount of work handled by the Government Printing Office Confidential Department also increased such as bank cheque books, betting tickets for the on-course bookmakers, debentures/share certificates, secure government documents, railway and road coach tickets. As well as tertiary entrance exam papers and State and Federal ballot papers which because of the massive print runs had to be undertaken on the main floor, additional security was put in place for the duration.

With this success and expansion, the ever-pervading tensions between the Government Printing Office and the private printing companies and the Liberal Government would again rise to the surface. However, the leadership and tenacity of Davies was instrumental at resisting the pressure of the then Liberal Brand Government to have the Government Printing Office outsourced to private industry, which had been part of their election promise to the Master Printers Association. For the time being, Davies’ operations and credibility survived internal investigation:

I therefore informed the government that I would be prepared to channel work to private industry provided in it could be proved that private industry were able to produce printing at an equal or better rate than the Government Printing Office, and in this regards I was investigated more often than Al Capone…He [investigator] departed satisfied that my costing system was definitely better than the Master Printers’ Association and I continued to produce all government printing work. 3

Although Davies was able to dampen the fires this time around and ensure that no government printing went out to private industry, this pressure would heat up again in the next few decades to boiling point.

The other event that would emerge was the rapid industrial changes that were neither easily predicted nor planned for. With this, the notion of a job at the Government Printing Office being considered a job for life and offering niche and specialist trade skills would also begin to be challenged.

3 Davies, Alexander Beverley, Oral History Interview, Chris Jeffery, c1987.

Shape up or ship out 1970-1990

Show moreApart from being much larger and with more staff, for anyone walking into the Government Printing Office’s Wembley factory in the 1970s/1980s, it would have appeared much the same as it had at Murray Street 100 years earlier, with much the same machinery being used and skilled trades being applied. Then, almost out of nowhere, the unprecedented growth of computerisation and automated technology was about to significantly impact on and change the printing industry, making it difficult to keep apace both in regards to equipment and skills. This was also the period which would see printing jobs finally being subcontracted and tendered out by the Government Printing Office to the private printing companies. Believing that this might ameliorate the historic private versus public printing battle, ultimately it only created new tensions. On top of this, there would be a major change in identity of the 100-year-old institution.

In 1971, Davies was ready to retire and step aside for the new Government Printer, William Brown. Davies’ reflections of his time in service in many ways pre-empted the next phase of the Government Printing Office:

It was a very friendly atmosphere in those days where basically everybody knew everybody and knew what their business was and I suppose that was indicative of the times, and we used to go on Chapel picnics and all those sorts of things and social functions. We used to have the printers’ ball which no longer takes place…I believe that in my last few years at the Government Printing Office that that wasn’t really there. That sense of family atmosphere had gone, because of the change of new technology. And certainly everybody was concerned about what their own future was, and people were leaving. 4

By the 1970s the Government Printing Office had around 400 people on staff and it was positioned as the major employer of apprentices in printing and manufacturing in Western Australia. The Government Printing Office had also become a highly unionised workforce, with 100% union membership for operational staff. This was not unique to the Government Printing Office, as a closed shop was the preferred operation for unions, not just in printing but for all manufacturing and in all factory environments. The Printing and Kindred Industries Union (PKIU) - essentially the rebadging of the WA Branch of the PIEUA in 1966 - represented all trades within the printing industry which at the time was about the fifth largest trades’ employer. However, as well as the PKIU and the Government Print Chapel, there were several other unions involved in negotiations to do with the Government Printing Office, and regular meetings were held between union, Chapel and management to work through the issues and process with representatives of the union always on site. They would monitor anything from wage claims to working conditions, and as soon as pay or conditions were causing ructions with either the unions and/or the workforce, negotiations started immediately and for anything that couldn’t be readily resolved it was straight into Industrial Relations. Sometimes stop work meetings resulted, usually held at large venues such as Leederville Oval, for example in 1975 when new pay awards were being introduced creating initial disharmony for employers.

A further increase to the workload came about when under the Labor Tonkin Government Treasury issued an instruction that all requisitions for printing be placed initially

with the Government Printer. Tonkin also introduced free text books for primary schools in 1972 which greatly expanded the print run of school texts. The Government Printing Office was also taking on more work from the Commonwealth Government departments based in Western Australia. With its huge pool of staff and increased printing work, the Government Printing Office factory at Wembley had in less than a decade become badly overcrowded and industrial strife was looming unless some relief from the poor work conditions was achieved. The solution – at least temporarily - was seen in the adjacent boys’ school buildings. The State Government made an offer to take possession of the school property in exchange for giving Marist College more land near their new high school campus in Churchlands on which to build a new junior school. Although it was hoped that the school building would become available by the end of 1975, delays in building the new school in Churchlands meant that the Government Printing Office could not take possession and make the necessary modifications until nearly the end of the school year of 1976. At the beginning of 1977, the new administration and publication sales offices were opened in the converted old school.

By the end of the 1970s, new technologies were starting to revolutionise printing methods and capacity, and traditional specialist skills were gradually being usurped and less manual labour required. In 1979, William Brown, together with his Deputy, William Benbow, introduced phototypesetting which had a great impact on the traditional hot metal composing and letterpress printing which eventually resulted in them only being used for some bespoke specialised work. With increased cost of labour and materials, the use of many of the styles of hand binding declined:

Customers are changing to cheaper, more simple styles to escape the high costs, which unfortunately do not allow apprentices the opportunity to learn a wide range of styles.5

However, the close-knit working force and sense of family and belonging that Davies alluded to a decade earlier was still there; it was still

‘… a good place, a very fair employer…every nationality worked at Government Print’.6

There was an active social club and staff still enjoyed their own canteen, social life was good, there were sporting teams such as the Government Print Cricket Club “the

Gov”, a soccer club, and indoor cricket teams, the GPs which was made up of staff from various departments such as male binders, office, large offset and even the new trades such as phototypesetting. The social club organised blood donation drives, picnics, sundowners, exercise classes, and the staff produced their own official newsletter – Type Eye. Although from a working perspective the trades remained strong individual units and looked after their own, there was still a sense of rhythm that united all trades, a seasonal pattern of tooling up and getting ready for the next big job. By 1981, the formerly male dominated trade apprenticeships were seeing the first female apprentices coming through in binding and finishing, printing and fitting and turning and therefore women were no longer only relegated to the unskilled trades as they had been for almost 100 years.

But more operational changes were looming on the horizon. A growing and substantial deficit in income and poor turnaround of work put the future viability of the State Printing Division again under scrutiny. However, all things considered, employees believed the Government Printing Office was running as well as it could given the old technology it had to contend with and were doing ‘…an honest days’ work and using the technology to its best capacity’.7 Even on pay day they kept their machine going while their pay was brought around. Some of this pressure was alleviated with up to 30% of the work handled by the Government Printing Office now starting to be subcontracted or tendered out to the private sector - both the jobs best handled by outside organisations as well as when demand was greater than its own resources.

Regardless, in 1984 the Labor State Government initiated the review of a number of its agencies and departments including the Government Printing Office. The main issues relating to the Government Printing Office included that it was not subject to any legislative base and had no restrictions on its scope of operations to run on a commercial basis even though it was restricted by financial arrangements imposed by State Treasury.8 In addition, though it was a sub-department of the Treasury, communication with the Government Printing Office was poor and as a result Treasury had little idea of what was happening in the day-to-day operations. For example, although Treasury issued a directive that all departments had to use the services of the Government Printing Office some departments were going out to private printers and also employing advertising agencies for design work which then ended up with private printers. This loss of work to the private sector was identified as needing to be redressed. In addition, Government Printing staff were also working in outside printing cells in which staff were working for and managed by other government organisations who had their own small printing divisions, and conversely other departments were neither being staffed or controlled by Government Print.

This complicated state of affairs were all investigated, and the Functional Review was completed in October 1986. In summary, the Government Printing Office was found to be an inefficient organisation in terms of both its work practices and machinery. Although it was acknowledged that its workforce was highly skilled, it was not seen as an essential function of Government as all work undertaken could be carried out by the private sector. However, rather than it being shut down, the direction decided by the Government switched from commercialisation to essentially a re-equipment program with many reforms to be implemented. At least for now, the Government Printing Office had not only avoided the chopping block but was going to become an even stronger force.

In line with the overarching functional review of other government departments and agencies carried out at much the same time, the restructure of the Government Printing Office operations also included being transferred from the State Government Department of Treasury to the Department of Works and Services. For the first time since its establishment, it was given the new name of the State Printing Division of the Department of Services, although the head of the division would still be known as Government Printer.

The recommendations of the Functional Review were finally approved by the Government in April 1987. A new Government Printer was appointed, Garry Duffield, who was charged with implementing the recommendations of the review, overseeing a reform program that included a substantial injection of capital into the State Printing Division to introduce state-of-the-art equipment combined with appropriate changes in management and a re-organisation of workflow patterns and practices that would make the State Printing Division a commercially viable organisation. Duffield’s proactive approach was not only aimed at changing the culture and efficiency but also to acknowledge that the organisation was the people, not just machines and paper.

The implementation of the reforms coincided with the loss of the telephone directory contract in 1987 to the private sector – not just for Western Australia’s printing division but nationally. This contract being such a significant part of its workload, its loss meant almost 200 workers from the State Printing Division eventually had to be let go, the immediate impact being on the casual workers hired especially for this contract. It also meant that there was a substantial amount of very expensive equipment no longer required. However, turning this into a positive, the sale of this surplus machinery would fund the purchase of new equipment. A major re-equipment program was therefore implemented immediately with new modern equipment approved for purchase of almost $5 million, to be installed in stages as part of a three-to-five-year capital works program.

The investment into the latest and best equipment would greatly improve operations but would also result in enormous shifts and changes to the organisation. A completely new management team was installed with the current management team either moved sideways or given different roles. A series of working parties were formed consisting of management and union representatives, tasked with making recommendations and initiatives in order to turn around the viability of its operations and make it a more service-orientated facility. The focus was to be on quality, competitiveness and productivity allowing for the State Printing Division to still compete in the commercial market, not just restricted to Western Australia but contracts could be sought nationally.

Another significant change was the relocation of the State Printing Division administration from the old Marist school building back into the main building in 1987. The old school then was converted into a new facility for the Western Australian School of Printing as the Wembley annexe of TAFE with classes commencing in 1989. The relocation of the WA School of Printing from St Georges Terrace in the city next to the State Printing Division proved beneficial with students undertaking printing apprenticeships having access to the best and most high-tech equipment available in the State and an operating production environment.

However, not everyone was happy with the change in fortunes of the State Printing Division. In 1988, a call was made for a further inquiry by the private sector, mainly by the Printing and Allied Trades Employers Federation (PATEFA), into the State Printing Division’s previous losses and inefficiencies and to freeze the purchase of any new printing equipment, demanding all government printing be handed over to the private sector, therefore the complete privatisation of its operations. PATEFA accused the State Printing Division of ‘…unfair tendering and said it threatened commercial printers’ jobs’. 9 So too the Liberal opposition joined to the debate alluding to the State Trading Concerns Act which precluded the Printing Division from producing revenue and competing with the private sector for business beyond the usual functions of State Government.

The Labor Government retaliated saying the printing industry ‘…was under pressure from desktop publishing, over capitalisation and lack of work from the private sector’ and that the commercial sector wanted the State Printing Division shut down only to prop up its own deficiencies and poor decisions.10 The capital works implementation was also defended by the Labor Government. In a letter from Gavan Troy, MLA, Minister for Labour, Works and Services, to Mr D P Scott, Printing and Allied Trades Employers’ Federation of Australia (dated 6 September 1988) it was noted that the capital works were to improve efficiency and modernise practices and procedures, not to increase the capacity of the work that could be done by the State Printing Division or increase its client base. It was also pointed out that currently, of its $30 million turnover, $12 million worth of work went to the private sector already through a tender process and about 25 percent of its remaining work (being approximately $4 million) was also subcontracted out to the private sector.

This did not appease the private sector and a massive campaign was launched by PATEFA – circulating a “survival kit” to its members and placing full page notices in the newspaper addressed to the taxpayers of Western Australia calling for State Printing Division to be closed. The Government responded by placing their own notices in the newspaper to reinforce the need for State Printing Division and counter the criticism, saying PATEFA’s campaign was driven by an election promise of the Liberal party to boost its election chances, and out of fear they would lose their share of the contract work if the State Printing Division continued and was allowed to upgrade. This latest agitation by PATEFA, on top of still adjusting and feeling threatened by the internal restructure, led employees of State Printing Division to once again take their grievances into the public domain and on to the steps of Parliament in September 1988.

The reforms according to the Functional Review, however, were upheld. By 1989, the plant modernisation program completed, and State Printing Division had become

the biggest printing works in Western Australia outside of the newspapers and one of the most modern printing concerns in the Southern Hemisphere. What used to take weeks or months to do could now be done in days. The revamped State Printing Division quickly became a completely self-sufficient, all-encompassing operation and business was thriving, printing an extensive range of products outside of its Parliamentary obligations such as train tickets (later multiriders), admission tickets to Royal Show as well as the stationary for WA Stamp duty and all the government Christmas cards including for the Governor. It was doing everything from making cloth covered boxes, blotting pads and photo envelopes, to mounting, rebinding and restoring, as well as wrapping. New initiatives were also introduced including the establishment of a Marketing and Sales branch, a Rapid Copy Centre and uniforms for staff. Planning and estimating/production also became a busy area and was considered an aspirational job; the first step on the ladder to a managerial position therefore providing further career options and opportunities.

These changes made the operations very successful and the State Printing Division became a leader in the printing industry with the training of apprentices and the introduction of Quality Assurance Certification to AS 3902 and ISO 9000 series, being the first major printing establishment in Western Australia to achieve such accreditation and certification. This again fired up the private companies, exacerbated by that fact that work opportunities across the printing trade and not just at the Government Printing Office were already diminishing. Even the

newspaper industry – hitherto a major employer of printing tradespeople and apprentices – was adopting computerised methods of typesetting which required far less staff and different training requirements. Linotype operators were particularly affected with the technological changes, not only because of having to learn and adjust to a completely new keyboard, which even the young workers coming through could operate, but with it the loss in their social status having once been regarded the most elite trade in the printing industry.

By the mid-1980s, the social aspects of working at the State Printing Division were also noticeably changing with the dances and picnics phased out and sundowners became more informal gatherings rather than ticketed events. This was not necessarily a unique evolution for the Government Printing Office but was a more universal trend particularly with stricter laws in drink driving. Also, the reduced staff numbers meant less people to socialise.

Despite the major overhaul and improvements made and increased efficiency, the printing trade across the board would still feel the effects of the continued acceleration of technological and industry changes and the State Printing Division was not immune to this. From the loss of the telephone directory to the introduction of new electronic publishing, laser printing equipment and computer technology, by the end of 1989 the State Printing Division workforce had reduced by nearly half in the space of two years.

4 Bucknell, Garry T, Oral History Interview, Chris Jeffrey, c1990.

5 Type Eye, October 1984 pp.7-8.

6 Meeting with State Law Publisher staff, 10 William Street, Perth, 27 June 2019.

7 Meeting with State Law Publisher staff, 10 William Street, Perth, 27 June 2019.

8 Government Printing Office of Western Australia, Functional Review, August 1984, p. 4. This arrangement with Treasury was unique to Western Australia as nearly all other State Government Printers operated on a revolving fund basis.

9 West Australian, 19 September 1988.

10 West Australian, 19 September 1988.

The final sundowner 1990-1995

Show moreWith the rebranding of the Department of State Services in 1990, another name change was imposed on the State Printing Division, this time being rebranded as State Print on 31 July 1990. Having achieved significant turnaround in productivity and profit as a result of the changes implemented in the wake of the functional review, it would appear that the future of the new State Print was secured. But again, outside influences were to have repercussions for State Print. By the early 1990s the number of binding, finishing and printing machinists employed in Western Australia were well below the national average. Printing apprentices were now drifting from traditional printing into IT operations. The engineers (fitters and turners) were also being downsized because machines were gradually being maintained by the suppliers. Staff numbers therefore continued reducing and even services such as the staff canteen closed and was replaced by a daily mobile food van.

Looking further afield, what was evident was that the operations of government printing offices were becoming a rarity across the country, with most of the other State Government Printing offices closed and the work taken over by the private sector. Being one of the last of the Government Printing services remaining, not surprisingly it again attracted the attention, and ire, of the commercial printing companies in Western Australia. This agitation from the private sector did not miss the attention of the Liberal opposition which in turn was starting again to raise the matter in Parliament. Although it was acknowledged that State Print had been keeping pace with the latest technology and had improved its efficiency and services, questions were asked about the need for the Government to have its own printing service. As the Functional Review of 1986 had shown, the work of State Print could more than ably be undertaken by private printing companies. The emergence again of this issue was, this time, not going to go away and would cause some of the most turbulent and troubling times for State Print and its people.

Other industrial sectors were also coming under scrutiny with the looming State Government election, including the institution that was the WA Government Railways Workshops at Midland, along with R&I Bank, State Government Insurance (SGIO) and Hospital and Laundry Services. This reflected not only the national government ideology of the day but a world-wide trend of transferring government assets to the private sector. The rationale was to ensure services were available but not necessarily to provide them. In February 1993, the State election saw the Liberal Party and its coalition partner, the Nationals, back in power with a stable majority. Although there were some pre-election promises made to the contrary, the Liberal Government had already made clear its position on privatisation. A “Discussion Paper” on State Print operations was quickly released also in February. The Discussion Paper presented a series of options for the future of State Print from complete closure to selling the whole service to varying levels of restructure of services and combinations of part sale/part retention. As a result, State Print was the first commercial operation of the Government to be offered up for sale. In late 1993, advertisements appeared in the daily press calling for "Expressions of Interest" from parties interested in purchasing the commercial operations of State Print. By the February 1994 deadline, nine submissions had been received.

Being a highly unionised and tight-knit workforce, it wasn’t prepared to go without a fight. On 16 March 1994, the “Great State Print Debate” was held at Wembley Lodge with business owners and the general public invited. A march was organised from State Print to the Lodge with workers carrying a coffin symbolising the death of State Print. Over 120 people from the community gathered in support of State Print which was considered a vital part of the local Subiaco business community with staff contributing to the economy of the Subiaco area. Appropriately, a speaker from Westrail was invited to talk about the effects of the closure of the Railway Workshops by the Government, in spite of pre-election promises that it would stay open. After this, State Print staff also organised a “Save our State Rally” at the Perth Concert Hall on 12 May 1994, for all the State Public Services.

Even if they were to lose the battle, the main things unions and staff wanted was to be offered redundancy or their permanent Public Sector employment be maintained as well as guarantees for redeployment and retraining. This was irrespective of the proposed Public Sector Management Bill which was due to be passed by Parliament and which would not permit this and therefore also contributed to the prevailing uncertainty and anxiety. The Community and Public Services Union gave Minister for Services, Graham Kierath, a deadline to respond or a strike would take place. Minister Kierath considered this industrial blackmail and that it only served to harm the negotiations and future employment of staff. Unsatisfied by this, a strike took place on the afternoon of 20 September 1994, followed by a series of work bans which impacted on productivity as was the intention. However, the privatisation had advanced to a point where there was no going back.

Not surprisingly, the years 1993 and 1994 were a time of unequalled industrial turmoil for the State Print staff; morale was low and there was enormous fear and uncertainty bearing down on them. Staff support services were initiated offering debriefing sessions and to put steps in place to help staff to deal with the imminent transition, but even more importantly to address stress-related symptoms that were already emerging. Inevitably a wave of requests for redeployment, retraining, severance as well as redundancy ensued. Along with natural attrition, this reduced the staff numbers from just under 300 in the late 1980s to now under 200, and more reductions to come.

But even the tender process to sell State Print was fraught and ultimately failed. Two main reasons accounted for this. One of the major impediments to the proposition was that the premises at Wembley were to be sold by the Government through the Subiaco Redevelopment Authority so the buyer would not only be outlaying for the business and machinery but have to provide its own premises. The pressure from industrial relations negotiations that were trying to look after the conditions and interests of the employees, combined with the Government pressure to secure jobs for as many of their future ex-employees as possible, was also perceived as a major stumbling block, on top of the Government wanting the best return from the sale.

Of the three companies who finally tendered all were eventually withdrawn, with none guaranteeing the number of jobs required, the best offer only promising to put on 5 apprentices. By November 1994, the Government cancelled the tender process for State Print to consider the decision to sell it privately or close it. Legal advice was sought to abort the tender process and negotiate a private deal. The choice was either sale by private treaty or selective tender process. In the end State Print was sold as a “Trade Sale” to the Coventry Group, a Western Australian company, making it the first and only Government Printery in Australia to be sold in this format as most previously had been closed and disposed of as an asset sale of plant and equipment.

Numerous meetings continued between workers and the now Labour Relations Minister Kierath, with workers calling for redundancy packages to be offered, insisting that they wanted to be made redundant from the Public Sector, receiving the full payouts due to them, then to move to the new job. However, once the sale was finally official, it was announced that no redundancy payouts as demanded would be offered, and all entitlements were transferring to the new company, with Minister Kierath pushing the line that they were keeping their jobs so there was no need for redundancies. This was a bitter blow to the remaining staff and made even worse when eventually only 12 weeks’ payout was offered regardless of length of service - even those who had been there all their working life - and with no preferential tax deduction imposed it was also fully taxed. Workers were also given the option to be redeployed within the Government and therefore retain their current level of pay and accrued benefits, however, opportunities would have been limited with staff from the former State Electricity Commission (SECWA) also seeking redeployment in addition to the many who were out of work from the closure of the WAGR Workshops. The other option was to stay at State Print but this would only be offered through a selection and interview process and the number of jobs being offered well below the current staff levels.

In mid-December 1994, an invitation was extended by Coventry Group to all employees of State Print to express their interest in joining the new enterprise. Around 60 positions were available, and current apprenticeship indentures could be transferred with negotiation. Coventry also announced they were going to organise a final Sundowner for all staff before the official handover. Although this was a valiant attempt to extend good will and signal the new era, the Sundowner would in many ways be the final nailing of the coffin that had been carried through the streets of Wembley by staff earlier that year.

The sale and official handover took place on 30 January 1995. The new company was called Allwest Print Pty Ltd which combined both State Print’s commercial arm and Mercury Press, a small printing operation already owned by Coventry. Of the 71 employees at Allwest, 45 were former State Print staff, including five apprentices as the obligation of training apprentices now fell on private enterprise, with another five staff joining them over the next few months.

At the time, the sale of State Print was considered the first successful sale of a government printing office in Australia, unlike the others that were akin to little more than a basic fire sale of assets and material. However, from an industrial relations perspective it was one of the most contentious of the privatisations by the State Government, and from a personal perspective it was very traumatic, especially for those who had been employed at State Print for years and even for their whole working life. For Coventry Group, the deal would ultimately not prove successful either. Although the sale essentially included the workforce and machinery, not including the buildings or land was to cause a great deal of consternation for the company and impacted on the growth and development of the business and client relations right from the start. In addition to this, with continued advances in technology in the print industry, much of the machinery purchased from State Print was quickly out of date and further investment would be needed.

Full circle 1995-2021

Show moreAfter an evolution of 125 years, on 30 January 1995 State Print officially ceased to exist. Out of the privatisation process, the Government retained a small part of the State Print operations, rebranding this discreet entity - in line with its core purpose - as the State Law Publisher. With only limited positions required and able to be offered, a total of only 27 staff were employed with the new organisation - two of which came from the State Government Bookshop which had merged with State Law Publisher in October 1994. In addition to the Government Printer the staff covered Operations, Sales and Editorial, and Financial services with previous workplace agreements cancelled and new ones drawn up. The remaining 96 employees of State Print who had not gone to Allwest Print were registered for redeployment.

When the State Law Publisher production section was being set up, it was apparent that to function effectively with a small team the members would need to be multiskilled and cutting across the various trades.This had been occurring in the smaller private sector print shops for years but previously considered grounds for demarcation disputes at State Print.

At the start there were two former Rapid Copy Staff running the printers and doing the finishing work. The prepress operators were trained in the operation of the printers and finishing processes to act as back-up to the printing staff. Over the years as staff left and the volume of work decreased, the prepress operators solely took over the role of printing and finishing along with their prepress functions.

Initially the production team had been covered by an agreement under the PKIU (which later amalgamated with the Amalgamated Metal Workers Union (AMWU)). This agreement was reviewed every four years. There was considerable time and effort on behalf of the union, staff, management, the Department of Commerce (who handled the negotiations on the Government’s behalf) and Industrial Commission involved every time the agreement was reviewed. Having the staff covered by the Public Service Award was seen as a way out of continually going through this long and often disruptive process. Consultations with staff, the AMWU, Community and Public Sector Union (CPSU), management and the Department of Commerce were conducted, the end result being the staff became covered under the Public Service Award.

The refined and restructured services continued to provide for the needs of Parliament, being responsible for the publishing and dissemination of legislation and statutory information including the Government Gazette, Industrial Gazettes and Public Service Notices as well as Bills, Acts, Regulations, and coordinate and sell government statutory forms and stationery. Some confidential services were maintained such as printing Government Commissions of Inquiry reports. The coordination of printing and distribution of the State budget papers was also undertaken.

Initially the State Law Publisher staff stayed on at Wembley until new premises could be secured. Allwest Print also started up their operations at Wembley, therefore the former colleagues were still working together at the same place but working for different employers with Allwest Print taking up most of the space and State Law Publisher operating out of one corner of the building.

In June 1995, the State Law Publisher began the move from Wembley to its new premises, returning to the city to an existing building at 10 William Street which was officially opened for business on 1st July. The move to William Street and the acquisition of up-to-date machinery resulted in operations becoming faster and more efficient, running from dusk to dawn in what was coined “continental shifts”. The printing staff worked three shifts over 24 hours to meet overnight Parliamentary support:

In the still of the night, when the rest of St Georges Terrace is in hibernation, the production room at the State Law Publisher is humming with machinery and the tapping of fingers on keyboards.11

In November of 1995, the Department of State Services was closed and the State Law Publisher was transferred to the Department of the Premier and Cabinet. In 1996, John Strijk who had been Acting Government Printer since late 1995, was officially appointed as the new Government Printer.

By November 1995 Allwest Print had moved out of Wembley, and on 7th November 1995 a formal inauguration ceremony was held at its newly purchased premises in Bassendean to acknowledge the completion of the new company’s first phase. Demolition of the former State Print factory at Wembley commenced immediately. However, the future adjustments and changes experienced by the staff who went to Allwest Print would prove even greater than those who stayed with State Law Publisher. As part of the privatisation process, the Government may have negotiated the transfer of entitlements and wages levels to the new employer, however, what it couldn’t guarantee was the sustainability of the new company. Less than two years after the sale, Coventry had already laid off 15 of the 48 former State Print staff. The was due to financial problems, some of which were caused by the cost of the new premises as well as the fact that most of the equipment that came from State Print was already out of date and soon after operations starting up had to be replaced. In 1997, Allwest Print was onsold by Coventry Group to Fairplay Print which was then purchased by Sands Print Group in 1998 but still operated under the name Fairplay. Although questions were raised in Parliament by the Labor opposition about the letting go of former State Print staff who originally went to Allwest Print, the response was that there was no way of safeguarding the entitlements that had been negotiated as part of the sale to the private company and, besides, the former staff were no longer considered the concern of the Government. Unfortunately, after just over 5 years of trading, Fairplay closed in 2001, and then Sands went into liquidation. The promises made to those 50 State Print staff for a future in private enterprise had all but extinguished and the last remnants of State Print ended.

But the former halcyon days at Wembley, of State Print and its massive pool of staff were not forgotten. On 11th February 2005, former and current workers organised a 10th anniversary function of the closure of the Wembley factory at the Old Melbourne Hotel. A Facebook page was also created for past staff to publish memoires and photographs and also to stay in touch, and regular reunions continued to be organised.

One last event was to occur which truly put a finality to the past presence of State Print at Wembley. In 2007 the School of Printing closed and the old Marist boys’ school - which also served as State Print’s administration building for 10 years - was subsequently demolished, finally removing all evidence of the former State Print from the Wembley landscape.

Technological advances with increased computerisation, the development of electronic databases, the internet, electronic transfer/dissemination of statutory information and digital publishing would continue to have an impact on the State Law Publisher and the printing industry in general. The publishing requirements for Parliament have remained but with publications now born digital and published online. Where once, between 3000-4000 copies of the Government Gazette were printed weekly, now only six are printed, one for the Department’s records, one subscriber and the others as legal deposits for libraries and archives. With rapid on-demand printing services, public requests for any documents such as Gazettes and legislation is done on a need’s basis. However, although the public could now print legislation from the legislation website online, to be considered a legal copy a document has to still be printed by State Law Publisher. Some outsourcing by State Law Publisher to private companies still continued, particularly in the production of work more suited to be produced using the offset printing process, with the State Law Publisher undertaking a contract management role to ensure the quality control and delivery of these documents to its clients.

The final last changes then rolled out in quick succession. Originally occupying the two floors of 10 William Street, staff and equipment were consolidated into the basement level of the William Street building in 2014. In March 2018, the responsibility for online publishing Western Australian legislation was taken over from State Law Publisher by the Parliamentary Counsel's Office within the Department of Justice. In July 2019, the William Street tenancy was closed completely and remaining staff and some equipment was moved to the State Government premises, Dumas House in West Perth. From its humble beginnings under the first Government Printer Richard Pether and his small team of seven men, the State Law Publisher has gone full circle and returned to a humble end with its team of six under the leadership of the Acting Manager, Kevin McRae.

In 2020, the Governor appointed the Parliamentary Counsel as Government Printer, commencing 14 September of that year.

With the Government Printer authorising Lit Support (TIMG) Pty Ltd, a commercial printing company, to print the legislation of Western Australia from 1 July 2021, the State Law Publisher has continued to provide printing services through to 30 June 2021. The ceasing of State Law Publisher operations at 30 June ends over 150 years of Government-run printing services in WA.

The Department of the Premier and Cabinet continues to produce the Western Australian Government Gazette which is published on the WA legislation website www.legislation.wa.gov.au

11Strijk, John 27 October 1997, copy script from Van Zeller and Associates provided by State Law Publisher.

Acknowledgments

Show moreThe following current and former staff at State Law Publisher for their time and assistance with the research and compilation of this history:

Kevin McRae

Allan Mathieson

Brian Cunnane

Brian Overste

John Strijk

References

Show moreArchive information held at State Law Publisher

- West Australian, 23 September 1988

- West Australian, 21 September 1988

- West Australian, 19 September 1988

- West Australian, 10 October 1989

- West Australian, 1 December 1994

- West Australian, 1 June 1996

- Reminiscence by Wm. Alfred Watson, no identification

- Strijk, John, Oral History Interview transcript, 30 October 2007

- Letter from Coventry Group Ltd to State Print employees, 10 December 1994

- Note from Under Treasurer to The Treasurer re. State Printing Division, 9 March 1988

- Letter from Gavan Troy, MLA, Minister for Labour; Works and Services, to Mr D P Scott Printing and Allied Trades Employers’ Federation of Australia, 6 September 1988

- Letter from L. W. Graham, Executive Director, Department of Services in Hotline: Department of Services Newsletter, Special Issue, 6 August 1990

- Dossier, March 1992

- Department of State Services, Forward Focus, Vol. 1 No. 3, November 14, 1994

- Strijk, John 27 October 1997, copy script from Van Zeller and Associates

- Allwest Print Pty Ltd, Print Vision, Issue No. 1, November 1995

- Government Printer Notes

- Buzza, J. “The Government Printing Office: A Brief History” in The Civil Service Journal, 20 July 1929.

- Garstang, E. J., ‘The Impact of Mechanical Typesetting and Gold Boom on Printing Craftsmen in Western Australia in the early 1900s’, unpublished research essay, n.d.

- Department of State Services, State Print: Steps in the privatisation process, prepared by Gary Habbishow, Acting Review Coordinator, Management Efficiency and Audit Services, April 1995

- State Print, Department of State Services Western Australia, ‘State Print Operations: Discussion Paper 1993’, February 1993

Primary Sources

Government Printing Office, Everything you wanted to know about Your Government Printing Office, n.d. (SLWA Library Ref 070.509 WES)

Government Printing Office of Western Australia, Functional Review, August 1984 (SLWA Ref: Q354.94100714WES).

Government Printing Office, Plan to Date 11 February 1922, PWD WA 22016 (SRO Consignment No. 1647)

Type Eye, official newsletter of Government Printing Office of Western Australia – available Government Printing Office of Western Australia Facebook page https://en-gb.facebook.com/pg/govtprint/posts/

Secondary Sources

Library and Information Services WA & State Printing Division, Parchment to Printout, brochure for exhibition, State Print, 1990 (SLWA Ref: Q686.209PAR)

Knox, Ron (ex Father of Chapel at Sunday Times, Perth), ‘Printing Chapels’, manuscript.

Pigeon, John, David Kelsall and Maxine Laurie, ‘Former Government Printing Office, Perth, Western Australia, Conservation Plan’, prepared for Christou Casella & Jee, 2000 (DPLH Library)

Sacred Ground; From Church School to Printing School, The Wembley Annexe of TAFE 9 Salvado Road Wembley 1954-2007: A brief history of the buildings and the Western Australian School of Printing, commissioned by Central TAFE as part of the Northbridge History Project, Abridged from a report by Susan Hall, editor Margaret Fowler, c2007 (SLWA Ref: 606.209SAC)

Articles and Journals

The Westralian Printer, “Printers’ Union First in W.A.” Vol. 1 No. 3, March 1952.

West Australian, 24 February 1899, p. 2.

Current interviews

Meetings with State Law Publisher staff, 10 William Street, Perth, 2019.

John Strijk, telephone interview 25 June 2019

Oral Histories

Davies, Alexander Beverley, Oral History Interview, Chris Jeffery, c1987 (SLWA Ref: OH2380)

Bucknall, Garry T, Oral History Interview, Chris Jeffrey, c1990 (SLWA Ref OH2346)

Websites and social media sources

Government Printing Office of Western Australia Facebook page:

https://en-gb.facebook.com/pg/govtprint/posts/

State Law Publisher website: https://www.slp.wa.gov.au/options/historfr.htm

Story prepared by

Extent Heritage Advisors for the Department of the Premier and Cabinet.