[This article contains images of people who have died]

Maisie Harkin is a member of the Stolen Generations who grew up in Aboriginal missions, trained and worked as a nurse, married and raised children. In her early life she was even observed by anthropologists.

Now she has grandchildren and a great grandson. But for most of her 87 years the Nanatadjarra woman had to get by without the basic identity document most Australians take for granted – a birth certificate.

Maisie had tried to get one without success. Not long after taking up residence in Kalgoorlie-Boulder in 2007, she sought to join her church group on a trip to Israel.

Without a birth certificate she couldn’t get a passport.

“The others, they went. (But) I didn't have that identification,” Maisie says. “I was disappointed because being brought up at the mission you were taught Christianity and being taught the Bible, we wanted to see what's over there.”

More recently Maisie tried again. A member of the Department of Transport’s remote services team put her in touch with Marnie Giles, Senior Community Engagement Officer at the Registry of Births, Deaths and Marriages.

“There are still lots of people whose birth isn't registered throughout the full spectrum of ages, from babies right through to someone of the wonderful age of Maisie,” Marnie says.

As often occurs in cases like this, Marnie turned to the Aboriginal History Research Services (AHRS) for help. With the applicant’s consent, this can provide access to records like those of the then Native Welfare Department and Aboriginal missions of the past.

But in Maisie’s case – and despite the records of the anthropologists – there still wasn’t enough information in the documents to register her birth.

But this time, her quest hadn’t reached another dead end.

Maisie says she was born with the help of traditional Aboriginal midwives in the Great Victoria Desert east of Laverton. The year was 1937.

Identified as the daughter of a white man, Maisie would have been a target of police raiding bush camps to take away the mixed-race children under the then policy of separating them from their families.

“We were in the bush, and the police were after us,” she says. “They knew we were around, but our people kept moving. To avoid the police.”

“They were bringing all the children back to Mount Margaret or to Mogumber.” Both were missions - Mogumber also known as the Moore River Native Settlement - which accommodated Aboriginal children.

Mount Margaret was also a ration depot where families could obtain food and essentials. Maisie says it additionally gave authorities the opportunity to keep records about individuals.

One visit by Maisie’s family is recorded in a 1941 letter from mission administrator Rodolphe Schenk to the Commissioner of Native Affairs in Perth. The document says they had “decamped and we know what where. They seemed to be frightened.” The letter is signed “Yours for Christ and the Natives”.

Some time later, Maisie became a resident of the mission and was given an English surname. “I know it was a grey, funny, rainy day that wasn't heavy rain, but sort of wasn't very pleasant day when I got in there,” she recalls.

She says she’s been told a mission record described her as “emaciated” on arrival. “We were given cod liver oil to build us up.”

Maisie was put under the care of older children at the mission, which became her home for more than a decade.

Asked what mission life was like, she says “terrible”. “We were stuck in this yard. We were the ‘part Aboriginals’, we weren't allowed to go out. You make your friends and, you know, you have some connections there.”

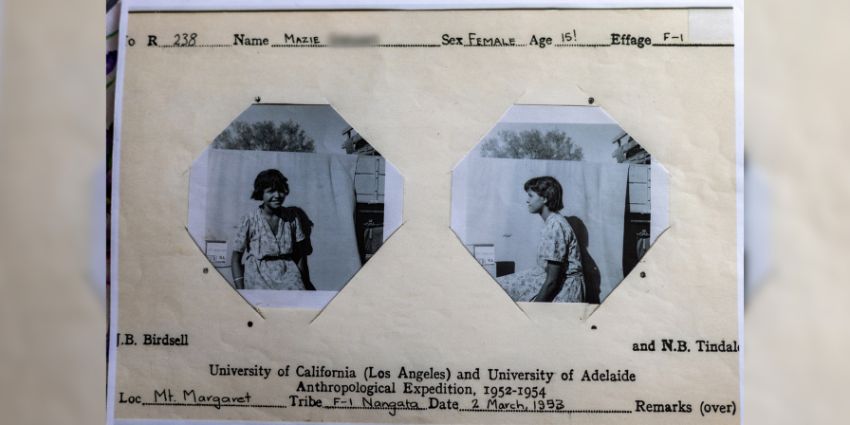

It was during these times that information about Maisie and her family were collected by famed anthropologist Norman Tindale. Photos of a teenaged Maisie appear in a profile by Tindale and associate Joseph Birdsell, captured during a 1953 expeditionary visit. An identifying number placed behind her, she faces the camera smiling in one and sits in profile in the other.

Maisie’s first name is misspelled and, next to age, one of the anthropologists incredulously wrote “15!”. A rough family tree drawn by expedition member Phillip Epling notes that Maisie is bound for Bunbury High School, some 1,000km away. “Socially is very well adjusted,” Epling wrote under her name.

While attending that school Maisie was accommodated at Roelands Native Farm, another mission for Aboriginal children near Bunbury. After school she embarked on her nursing career, working in Perth and Melbourne.

While her life was documented, Maisie’s birth details remained something of a mystery. Determined to leave no stone unturned, the Registry’s Marnie went back to the AHRS and asked them to take another look.

“I was able to meet with one of the very experienced researchers and he had a little bit of a light-bulb moment where he was able to pull out a document that hadn't been looked at before,” Marnie says.

That document was an admission record from Mount Margaret. “And within that, we were able to find a date of birth and her mum and dad, and we were able to register from that.”

Thrilled, Marnie called Maisie to break the news. “It was really lovely,” Marnie says. “She was really pleased.”

On obtaining a birth certificate at 87, Maisie says: “I was amused.” Hearing about it, a friend had ribbed her that she was no longer an “alien”.

“It's good to get it,” she adds. “Now I can get on the plane without using all the other IDs. And when you go to Perth, if you're going to stay at a motel or something, you have to have that one main identity thing.”

Marnie credited the successful outcome in Maisie’s case and those of others to the expansion of the Registry’s community engagement team and support of its management.

“We now have capacity to be able to do the research, to know who to ask and leverage the connections that we've made because of the travel and the work that we do.”

Critically for Maisie, having an identified place of birth has enabled her to visit her Country, which now sits inside a mining precinct. “I'm connected to that land and it's important. That's why the people go back to the land.”