This page contains information relating to historical forced adoption practices that may be confronting or distressing.

On 22 February 2023 the Standing Committee on Environment and Public Affairs commenced the Western Australian Inquiry into past forced adoptive policy and practices (the Inquiry). On 22 August 2024 the Inquiry released Report 66 – Broken Bonds, Fractured Lives: report on the inquiry into past forced adoption in Western Australia (Report 66 – Broken Bonds, Fractured Lives) in the WA Parliament. Information in this section is drawn from Report 66 – Broken Bonds, Fractured Lives.

Forced Adoption

Forced adoption occurred from the 1930s to the 1980s and refers to the unethical and often illegal removal of babies from their mothers.*

(*Forced adoption: Department of Social Services).

It represents a significant system of failures by authorities and those in positions of power to safeguard the parental rights of mothers and fathers and prioritise the best interests of children.

Historical forced adoption policies and practices are estimated to have affected 250,000 Australians. In Western Australia, the number of adoptions peaked during the 1960s through to the mid 1970s, with around 90% of those adoptions being of children of unmarried mothers.

Under forced adoption policies and practices, unmarried women were channelled into an adoption process, often early in their pregnancies, and sometimes without their knowledge. These practices were carried out by the former Departments of Communities, which were directly involved in all adoption applications from 1959. Report 66 – Broken Bonds, Fractured Lives found some staff engaged in unethical practices and misconduct.

Private solicitors, public hospitals and maternity homes were also found to be directly involved in forced adoption practices, including:

- King Edward Memorial Hospital

- Ngala (previously Alexandra Home)

- Hillcrest, run by the Salvation Army

- St Anne’s Maternity Home

- Catherine McAuley Centre.

These institutions were involved in arranging adoptions and worked alongside the former Department of Communities. Practices included:

- Maternity homes subjecting women to harsh conditions, including emotional abuse and unpaid labour.

- Forcibly restraining mothers during birth.

- Providing mothers with poor, and at times medically violent and negligent, medical care.

- Forcibly separating mothers from their newborn babies immediately after birth.

- Denying mothers their request to see and hold their newborns.

- Pressuring or coercing mothers into signing consent forms, including coercive practices such as denying mothers access to their baby until they sign the consent to adoption form.

- Disrupting and preventing babies from forming an attachment to their mother.

- Providing false or misleading information to mothers about the exercise of their legal rights.

- Fathers being prevented from visiting mothers and being excluded from any information or decisions relating to the pregnancy, birth or adoption of their child.

- Newborn babies left in institutional care, sometimes for months, while an adoptive family was sought.

- Changing the name of the adopted infant and/or child, changing their birth certificate which erased their identity at birth, and preventing access to their original birth certificates.

Other State Government agencies also played a role in past forced adoption. For example, some staff employed at the courts engaged in unethical and improper conduct when dealing with mothers signing consent documents. This assisted in and facilitated the coercion of unmarried mothers to consent to the adoption of their children.

The impact of these practices has been profound and lifelong. Many mothers endured lifelong trauma and grief after being separated from their children under duress. Many adopted people experienced lifelong trauma and grief from forced separation, and a loss of identity and family. Lives were fractured and the lack of transparency and support compounded the trauma experienced by mothers, fathers, adopted people and their families, despite their resilience.

Trauma can impact an individual’s mental, physical, social, emotional, and spiritual wellbeing. People who have experienced forced adoption describe experiencing significant stressors that can become more intense at certain life stages or at times of significance, such as a birthday or when a grandchild is born. Certain environments and interactions can contribute negatively to a person’s ongoing wellbeing, including health care settings or social messaging that reinforce adoption as a positive experience and one to be grateful for. For adopted people, not knowing their family connections and history, including medical history, can have a profound impact on their sense of identity, belonging, and health.

This severing of family and identity lead some mothers and adopted people to undertake courageous attempts to locate their lost family. These searches, driven by a deep sense of loss and hope, sometimes span years and involve significant emotional, financial and practical challenges. When families do reunite, reactions can be mixed, as complexities arise from blending families after a lifetime of separation.

Forced adoption policies and practices were wrong and illegal and have caused irreversible pain and suffering to those who experienced them. It is vital we learn from the past and ensure past wrongs are never forgotten and never repeated.

Forced Adoption Timeline

This timeline is a summary of key events that provide context to historical forced adoption in Western Australia. The information in this timeline is extracted from Report 66 – Broken Bonds, Fractured Lives and other sources as referenced. It provides a summary of an interpretation of the effect of the legislation and is not a definitive statement of the law.

1896

Show moreAdoption of Children Act 1896 (WA)

WA was the first jurisdiction in Australia to pass legislation relating to adoption, with the Adoption of Children Act 1896 (WA). The passing of this legislation meant Adoption Orders were made by a judge of the Supreme Court. Consent requirements were:

- Consent of the child if they were over the age of 12.

- Consent in writing from both living parents.

- If the child had been ‘deserted’ no consent was required.

The Adoption Order granted the surname of the adoptive parents to the child, in addition to their name at birth. This meant the child would have a double-barrel surname.

1920s

Show moreLegislative Reform

There were four amendment Acts passed during the 1920s. Significant reforms included:

- Removal of the requirement for a child to retain their name at birth, and instead only the adoptive parent’s surname was included in the adoption order. This decision favoured adoptive parents, who were pushing for this change.

- Records for adoption proceedings were closed to the public, contributing to the closed adoption era.

- Adoptive parents could apply to have the adoption details included on the registry as a new birth entry. This amendment meant many adopted children would have two birth certificates:

- The original birth certificate that included their name, date and place of birth, and names of their parents.

- The second birth certificate that had their adopted name, date and place of birth, adopted parent’s details, and a reference to the order of adoption.

It was this second birth certificate that became the child’s official birth certificate, essentially erasing the details of their identity and family at birth.

1940s

Show moreLegislative Reform

There were two amendment Acts passed during this time. Key reforms prioritised the rights of adoptive parents and further removed the rights of parents. Adoptive parents could now choose to give the child a new ‘Christian’ name at the time of the Adoption Order, making the process easier. Previously, to change the first name of an adopted child, adoptive parents would need to apply under the Change of Names Act. Once an Adoption Order was granted, the new birth entry was automatically registered, replacing the need for adoptive parents having to apply for this.

Consent provisions introduced included:

- Judges no longer needed consent from a child over the age of 12 in special circumstances. The child not being aware of being adopted was given as an example of a ‘special circumstance’*

(*Parliament of Western Australia, Adoption Legislative Review Committee WA, Final Report – A New Approach to Adoption – Adoption Legislative Review Committee February1991). - A judge could dispose of the consent required from the father for all children where the parents were unmarried.

- A judge could dispose of the consent of a parent or guardian where it was deemed they were ‘unfit’ to care for the child and they had been given notice of the adoption application.

1950s

Show moreLegislative Reform

Key amendments during this time included:

- A judge’s discretion to dispense with the consent in writing of the parents or guardian was significantly broadened.

- A judge was no longer required to record their reasons for dispensing with consent on the Adoption Order.

- The former Department of Communities was required to provide a report as to the suitability of potential adoptive parents for all adoption applications. This meant, from 1959 the former Department of Communities was now involved in all adoption applications.

Changes to legislation during this period supported closed adoption, erased the child’s identity, limited parents’ rights and promoted the rights of adoptive parents.

United Nations Declaration of the Rights of the Child

In 1959, principles in the United Nations Declaration of the Rights of the Child included:

- Principle 2: highlights the best interests of the child as paramount.

- Principle 4: ‘…special care and protection shall be provided both to him [infant] and his mother, including adequate pre-natal and post-natal care.’

- Principle 6: ‘the child, for the full and harmonious development of his personality, needs love and understanding. He shall, wherever possible, grow up in the care and under the responsibility of his parents…a child of tender years shall not, save in exceptional circumstances, be separated from his mother*.’

(*United Nations General Assembly, ‘Declaration of the Rights of the Child’, 841st plenary meeting, 20 November 1959, Resolutions adopted in the reports of the third committee, General Assembly - Fourteenth Session, accessed 12 August 2025, p 20).

The Declaration was not a legally binding document; however, it signifies broadly accepted principles relating to child rights including the importance of children, particularly young children, to remain with their mother.

1960s

Show moreModel Legislation

The Commonwealth Government and the states developed model legislation that aimed to create consistency in adoption practices across jurisdictions.*

(*Commonwealth Contribution to Former Forced Adoption Policies and Practices – Parliament of Australia)

The Senate Inquiry report on the Commonwealth Contribution to Former Forced Adoption Policies and Practices (Inquiry Report) found that the provisions were intended to reflect the best interests and welfare of the child, and that mothers were fully informed prior to giving consent.

However the Inquiry Report also found the model legislation supported closed adoptions and was informed by ‘clean break’ theory.

Clean Break Theory

‘Clean break’ theory was based on the idea a newborn child is a ‘blank slate’ and their characteristics are formed by their environment rather than their genetics.*

(*Clean Break Theory | Find and Connect)

The theory promoted a ‘clean break’ for a newborn baby born to an unmarried mother was in the child’s best interests and beneficial to their development. The theory implied separation as early as possible was in the child’s best interest and informed many adoption policies, practices and legislative amendments at the time.

Report 66 – Broken Bonds, Fractured Lives found in practice, ‘clean break’ theory was applied inconsistently, and it was not universally supported at the time. There was considerable research that highlighted the importance of the mother-child bond, and the grief, pain and trauma separation could cause for mother and infant.

Further information on ‘clean break’ theory and its’ impact on mothers and their babies can be found in Report 66 - Broken Bonds, Fractured Lives, Chapter 5, ‘New mothers and babies’.

1970s

Show moreIn the late 1960s and into the 1970s parents and adopted people began to demand the right to access adoption records, which were of such deep importance to them as individuals. Results of research into the implications of secrecy in adoption, and declining social and financial discrimination directed against single women and their babies assisted in their advocacy.*

(*Parliament of Western Australia, Adoption Legislative Review Committee WA, Final Report – A New Approach to Adoption – Adoption Legislative Review Committee February1991 at page 55 para 2.6).

Legislative Reform

A series of amendments were introduced in 1964; however, they only became operational in 1970. The amendments broadly aimed to:

- Safeguard the welfare of children.

- Safeguard the rights of adoptive parents.

Consent provisions included:

- Consent from a mother could not be given within seven days of giving birth, unless a medical practitioner or midwife confirmed that mother was in a fit state at the time of signing consent.

- Consent from an unmarried father was removed all together.

- A mother could revoke her consent within 30 days of signing the consent. Prior to this a mother could revoke her consent at anytime before the Adoption Order was granted.

Report 66 – Broken Bonds, Fractured Lives indicates the Inquiry found evidence of consent from some unmarried mothers was forced and coerced, and no evidence of any revocation of consent by a mother being accepted between 1920 and 1990, despite mothers seeking to apply.

Further information on consent in the forced adoption era is available in Report 66 - Broken Bonds, Fractured Lives - Chapter 6, ‘Consent, permanent separation and placement’.

Further Legislative Reform

There were a suite of amendments throughout the 1970s. Broadly the amendments outlined the role of the former Department of Communities (the Department) in adoptions, including their reports being conclusive evidence for judges of the suitability of prospective adoptive parents, changes to the type of information in the reports, the Department’s role in caring for children and making decisions about children who were wards of the state prior to being adopted, and removing personal liability of any officer, Director or Minister who carried out duties under the Act.

Consent requirements were tightened so that certain persons, such as Department welfare officers or the prospective adoptive parents’ solicitor, could no longer attest to the signing of a birth mother’s consent.

The welfare and interest of the child was introduced as the paramount consideration for all purposes under the Act.

Other amendments included broadening the offences related to identifying any person involved in an adoption and limiting the ability to change the first name of a child who is over 12 years of age.

On 1 June 1976 the Family Court of Western Australia opened and all applications for adoption were now made to the Family Court, instead of the Supreme Court.

Supporting Mother Benefit

In 1973 the Commonwealth Government introduced the ‘Supporting Mother Benefit’. The aim of this was to support single mothers. However, for some mothers forced adoption practices meant information about financial assistance was not provided consistently or clearly. In 1977 this benefit was replaced by the ‘Supporting Parent’s Benefit’, which extended the payment to all single parents, including fathers. The introduction of this payment supported many mothers to keep their children, and Australia saw a decrease in the number of adoptions.*

*(Supporting Mother's Benefit | Find and Connect)

Hillcrest Maternity Home

Hillcrest Maternity Home closed in 1974.

Federal Family Law Act

The Federal Family Law Act introduced the ‘best interests of the child’ as the paramount consideration in adoption decisions.

Royal Commission on Human Relationships

The final report of the Royal Commission on Human Relationships was published in 1977.*

(*Royal Commission on Human Relationships).

This noted concerns about the adoption process, including coercion of young mothers and the lack of informed consent.

1980s

Show moreLegislative Reform

Further amendments were made in 1980 and 1985. Key changes included:

- A judge could dispense the requirements to give notice to the surviving members of a deceased spouse’s family, when seeking to apply for an adoption.

- A child now automatically received the adoptive father’s surname. Previously this was a decision of the adoptive parents. If the child was over 12 years of age, they continued to use their existing surname if this was the child’s preference, and the judge considered it in their best interest.

- Adoption could only be arranged by the former Departments of Communities, or an approved adoption agency.

- An adopted person could apply for an extract of their original entry of birth. Counselling was required before the information would be provided.

- The ‘Adoption Contact Register’ was introduced allowing people to register their wishes in relation to sharing information and making contact. If a parent registered an objection to their information being shared, an adopted person could not obtain their original entry of birth.

Maternity Homes

St Anne’s Maternity Home was officially renamed St Anne’s Mercy Hospital in 1982. In 1997 the hospital was renamed Mercy Hospital.

Ngala Mothercraft Home and Training Centre Inc (formerly the Alexander Home), the last of the maternity home services, closed.

1990s

Show moreAdoption Act 1994

The Adoption Act 1994 (the Act) replaced the Adoption of Children Act 1986. The introduction of the new Act promoted an era of open adoption within a highly regulated framework. The Act recognises the right of every child to know their family and culture of origin and encourages contact between all parties to an adoption. The Act is guided by the principle that the welfare and best interests of the child must always be the paramount consideration in adoption decisions.

To facilitate open adoption, the Act introduced Adoption Plans that guarantee the rights for parents and adopted people to maintain ongoing contact and connection. Western Australia was the first jurisdiction to legislate and implement Adoption Plans.

The Act initially included provisions for contact vetoes and information vetoes. Contact vetoes allowed a person who was party to an adoption to lodge an objection to being contacted by others connected to the same adoption. Information vetoes allowed a person who was party to an adoption to lodge an objection to their identifying information being shared with another person connected to the same adoption.

Vetoes were a barrier to people being able to access adoption information and records and impacted a person’s ability to learn about their family, identity and life story.

National Principles in Adoption

In 1993 the National Principles in Adoption were developed and ratified through the Community and Disability Services Ministers’ Conference. In 1997 they were updated to include Australia’s obligations under the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child and the Hague Convention on the Protection of Children and Co-operation in Respect of Intercountry Adoption.

The principles promote open adoption, the rights and best interests of the child as paramount in all decision making, and access to adoption information and records.

Bringing them Home

In 1997 the Bringing them Home: Report of the National Inquiry into the separation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Children from their Families (the Report) was released.

It considered the forced removal of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people from their families, known as the Stolen Generations, and made 54 recommendations.

The Report refers to adoption practices, reporting:

‘Adoption was another method of removing Indigenous children from their families. Mothers who had just given birth were coerced to relinquish their newborn babies. Those whose children had already been forcibly removed were pressured by Board officials to consent to adoption. The Child Welfare Department processed the adoption but relied on Board officials to obtain the mother’s consent. The Child Welfare Department did not check to ensure that Indigenous mothers understood they were being asked to agree to the permanent removal of their child.’*

(*The Report | Bringing Them Home p.40).

The Report also found instances of incorrect information being provided to people who thought they, or their child, were adopted. During this era Aboriginal children could be forcibly removed without legal orders. This meant, some people were told they were adopted, however no Adoption Orders were granted.

2000s

Show moreAdoption Amendment Act 2003

Key amendments to the Adoption Act 1994 included:

- No new information vetoes could be placed from 1 June 2003, and the effect of any registered information vetoes ceased after January 2005.

- No new contact vetoes could be placed from 1 June 2003.

These amendments have significantly contributed to improving access to adoption records and information.

Forgotten Australians Report

The Forgotten Australians: A report on Australians who experienced institutional or out-of-home care as children was released in 2004. The report focused on the experiences of children who were in institutional and out-of-home care, mainly from the 1920s until the 1970s. The report uncovered widespread ‘…abuse and assault across institutions, across States and across the government, religious and other care providers.’*

(*Forgotten Australians: A report on Australians who experienced institutional or out-of-home care as children - Parliament of Australia, p. xv).

Chapter four of the report specifically looked at the treatment of teenage girls who became pregnant and the forced adoption of their babies. Thirty-nine recommendations were made including apologising for past practices, improving access to information and records, improving support and counselling services, and increasing public awareness.

A second report was released that covered children’s experiences in foster care.

2010s

Show moreImpact of Past Adoption Practices Australian Research

In March 2010 the Australian Institute of Family Studies published its’ final report Impact of past adoption practices: Summary of key issues from Australian research commissioned by the former Australian Government Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs.

The purpose of the report was to review existing research about past adoption practices in Australia. Key themes identified included: viewing past adoption practices as trauma; coercion, secrecy and silence; the impact of adoption on extended family members; and the importance of counselling and support for those affected by past adoption practices.

Western Australian Government Apology

On 19 October 2010, the then Premier of Western Australia Colin Barnett apologised on behalf of the Western Australian Government to people affected by forced adoption or removal policies and practices.

Senate Inquiry

On the 15 November 2010 the Inquiry into the Commonwealth Contributions to Former Forced Adoption Policies and Practices is referred to the Community Affairs References Committee.

Senate Inquiry Report Released

In February 2012 the Australian Government released its report Commonwealth Contribution to Former Forced Adoption Policies and Practices. The report found that forced adoption policies and practices were widespread throughout Australia and made 20 recommendations, including recommending the Australian Government apologise.

Adoption Amendment Act 2012

A key amendment in 2012 to the Adoption Act 1994 was the removal of the offence relating to the breach of a contact veto. This amendment decriminalised contact between parties involved in an adoption where a contact veto was in place.

Further amendments included allowing for birth siblings over 18 years old to have access to identifying information, provided the adopted person was also over 18 years old. This amendment contributed to improving access to adoption records and information.

National Research Report

In August 2012 the Australian Institute of Family Studies released its report Past Adoption Experiences: National Research Study on the Service Response to Past Adoption Practices. The study aimed to improve understanding of the effects of past adoption policies and practices. The perspectives of mothers, fathers, adopted people, adoptive parents, other family members and service providers were included. The study particularly focused on the need for a well-informed workforce and specialised services, and to increase community awareness about past adoption practices.

Australian Government Apology

On 21 March 2013, the then Prime Minister Julia Gillard apologised on behalf of the Australian Government to people affected by forced adoption or removal policies and practices.

Forced Adoption History Project

In March 2014 the National Archives of Australia launched the Forced Adoptions History Project. The project aimed to increase awareness and understanding of forced adoption practices and to identify and share experiences of forced adoption. The project provided opportunities for individuals to share their personal experiences and to read about the experiences of others. An important part of the project was the Without Consent: Australia's past adoption practices exhibition that toured Australia to increase public awareness about past forced adoption practices.

2018 Statutory Review of the Adoption Act 1994

A review of the Adoption Act 1994 was undertaken by the Department of Communities with the support of a reference group. The review made 31 recommendations including legislative changes and policy and practice improvements. All five of the non-statutory recommendations have been implemented. The report of the Review was tabled in Parliament on 21 November 2018 and can be accessed online.

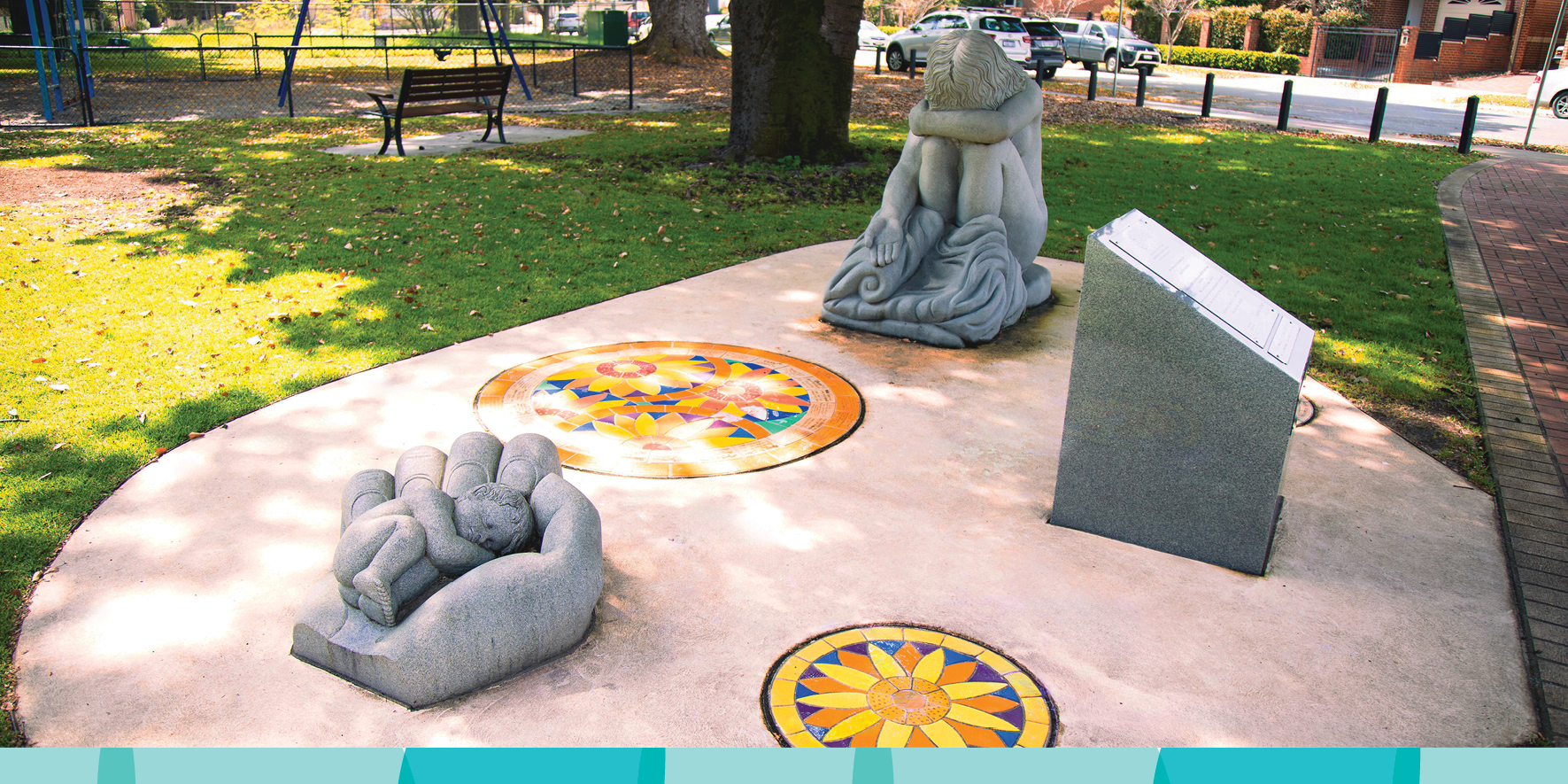

Empty Arms – Broken Lives Memorial

On the 21 March 2019 the forced adoption memorial in Western Australia, Empty Arms – Broken Lives, was unveiled in the Town of Victoria Park to mark the sixth anniversary of the national apology offered by the Australian government on 21 March 2013.

The memorial was commissioned by the Association Representing Mothers Separated from their Children by Adoption, known as ARMS, and was funded by the Australian government. These sculptures are a symbolic acknowledgement of the pain and trauma suffered by all people separated by forced adoption. You can visit the memorial at Read Park in Victoria Park.

2020s

Show more10th Anniversary of the National Apology

The 21 March 2023 marked the 10-year anniversary of the national apology. The Australian Government hosted commemorative activities in Canberra for those affected by past forced adoption policies and practices and the services working to support them.

Parliamentary Inquiry into Past Forced Adoptive Policies and Practices in WA

From 22 February 2023 to 22 August 2024 the Standing Committee on Environment and Public Affairs conducted an Inquiry into past forced adoptive policies and practices in Western Australia (the Inquiry). The Inquiry received 165 submissions from people with lived experience of forced adoption as well as service providers and other professionals. The Inquiry found historical policies and practices facilitated the forced separation of mothers, fathers, and their children, inflicting profound harm and causing lifelong pain and trauma.

On 22 August 2024 the Inquiry released Report 66 – Broken Bonds, Fractured Lives: report on the inquiry into past forced adoption in Western Australia into Past Forced Adoption in Western Australia that made 39 recommendations, 36 of which were directed to Government.

On the 22 October 2024 the Government tabled its response to Report 66 – Broken Bonds, Fractured Lives, including support for 19 recommendations to address the impact of past forced adoptions.

Forced Adoption Reference Group

Arising from a recommendation in Report 66 – Broken Bonds, Fractured Lives, the WA Government announced the establishment of the Western Australian Forced Adoption Reference Group (Reference Group).

The first meeting was held on 13 June 2025. The Reference Group has 13 members, 12 of which have lived experience of forced adoption. The Reference Group is established to ensure people with lived experience of forced adoption have a central role in shaping legislation, policies and practices that impact them.